China currently is certainly at the forefront of pushing technology to the next level.

And this is also the fact in its restaurant industry!

For once China wins awards for originality as this tech meets fine dining concept was first seen in Shanghai and then promptly copied by the well known Spanish restaurant Sublimotion. It is of interest to note how Sublimotion managed to copy the concept and offer it at more than twice the price of the original model.

At the venue we will be reviewing Only 10 guests can eat at this Michelin-starred restaurant per night, where a meal costs $600 and the dining room is transformed by high-tech lights, sounds, and scents throughout the evening.

The avant-garde restaurant in Shanghai offers an immersive, multi-sensory experience to only 10 diners per night.

Ultraviolet, opened in 2012 by French chef Paul Pairet, claims to be the first experimental restaurant of its kind. The dining room, which has a single table and bare white walls, is transformed throughout the meal by lighting, projections, sounds, and scents, transporting diners from an abstract otherworldly setting to an autumn forest to a rainy day in London.

The meal, which includes 20 courses and a drink pairing, starts at about $600 per person and can cost up to $860 on certain days of the week.

Ultraviolet seems to follow an emerging trend of defining luxury as a unique, exclusive experience rather than just an expensive one. CEOs are paying to go on extreme adventure retreats for soul-searching; the ultra-wealthy buying permanent apartments on cruise ships that travel the world following major events including the Olympics, Wimbledon, and Carnival in Rio de Janeiro.

Although anyone can book a seat at the restaurant and reserving the entire table isn’t necessary, it’s notoriously tough to get a reservation, according to Eater.

The restaurant attracts foodies, both locals and travelers, a representative for the restaurant told Business Insider.

Here’s a look inside Ultraviolet.

Ultraviolet was created by famous French chef Paul Pairet. The walls of the restaurant’s dining room are bare and white, with no décor, paintings, or windows — only a single table and 10 chairs.

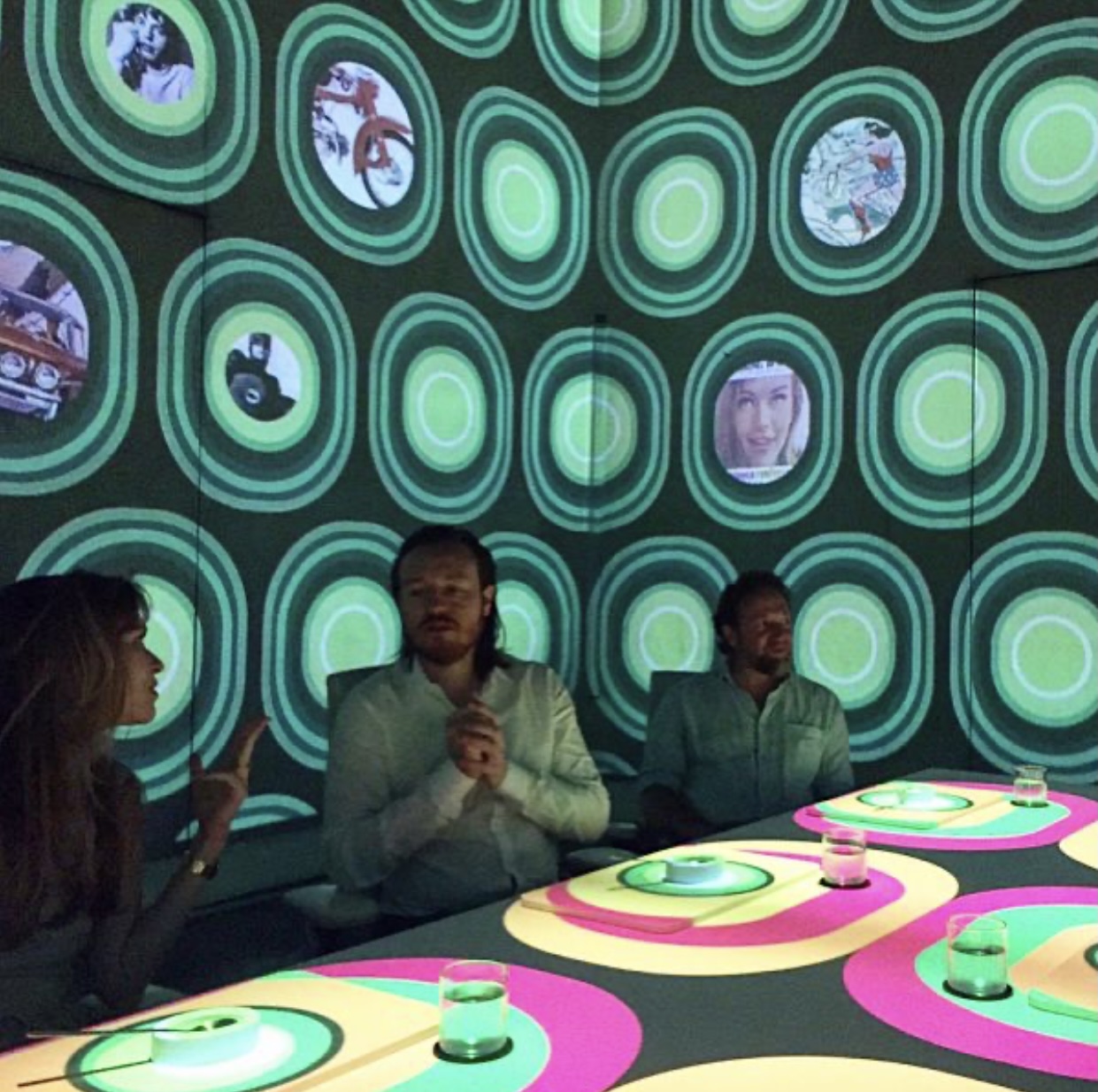

But during the meal, the room is transformed by light, sounds, and scents. This version of the room, called “Autumn Soil,” resembles an enchanted forest.

The experience unfolds as a play. Food leads. Each course is enhanced with its own taste-tailored atmosphere: lights, sounds, music, scents, projection, images and imagination… and food,” reads Ultraviolet’s website.

The technology, which includes lights, projectors, dry scent diffusers, infrared cameras, and a surround sound system, is controlled remotely from a “Techno Room.”

One scene boasts a transformation into a shadowy forest in autumn colors. Another room evokes a rainy day in the United Kingdom.

In another scenario, “Pop Center” displays rows of brightly-colored, familiar pop culture images.

Diners can either share the 10-seat table with other guests or reserve the whole table as a group.

Ultraviolet claims to hold one of the world’s record ratios of employees per guest, with 2.5 staff members to each guest.

New York Times columnist Frank Bruni ate at the restaurant in 2013 and found the food to be excellent, writing “… just when all of this starts to feel too gimmicky, too fast, too much, [Pairet] slows everything down for three relatively straightforward main courses — of sea bass, rack of lamb and Wagyu — that have a classic French pedigree and leave no doubts about his mettle as a cook. They’re a pivotal breather, and they were breathtaking.”

Opened in 2012, Ultraviolet is advertised as “the first restaurant of its kind uniting food and multi-sensorial technology.”

Pairet, the chef, wants the restaurant to be anything but pretentious. “Ultraviolet is hopefully about doing things seriously without taking oneself too seriously,” he wrote on the website.

The ultra Violet idea allegedly gets stolen

In May 2012, Paul Pairet, a charming but controlling French chef, now 51, opened a restaurant in Shanghai called Ultraviolet. The concept had been in his mind since as early as 1996 and in an email pitching the idea to a possible backer dated December 19 2004, Pairet laid out his vision for a lavish dinner of 14 courses accompanied by “unparalel [sic] technical possibilities”.

The project began to crystallise into what would eventually become Ultraviolet: an all-white restaurant for 10 diners with high-definition projectors altering the surroundings as they eat. It was placed third in this year’s list of Asia’s 50 Best Restaurants.

Pairet, who also runs Mr & Mrs Bund, a sumptuous French bistro at number 18 on a promenade by Shanghai’s Huangpu river, invited the celebrated chef Alain Ducasse to a special preview. “I told him [Pairet] that it was magnificent and delicious,” says Ducasse. “The harmony between the performance and the substance is just perfect. The audiovisual effects are never meaningless; they are a frame which underlines and exhilarates Paul’s very personal and tasty cuisine.”

Guests at Ultraviolet meet at Mr & Mrs Bund at 7pm for the beginning of what will be a three- to four-hour dinner. After an aperitif, they board a bus that winds through Shanghai’s old Hongkou district, deliberately meandering to discombobulate its passengers. Eventually it deposits them outside a warehouse on Suzhou Creek, where a woman sweeping the street points the diners to an unmarked door.

Stephan Pyles, who ate at Sublimotion a month after dining at Ultraviolet, can be forgiven for feeling a sense of déjà vu. Various details of the Spanish restaurant first appeared in Shanghai: inside Ultraviolet, the walls are white, the table is white and the chairs are white. Names are projected on to the table from an unseen source (another touch that also appears at Sublimotion).

Sometimes the food is exaggerated to the point of being ridiculous. “Is it a game or a meal?” asked Frank Bruni, the former New York Times restaurant critic who visited in 2013. For one course, a Union Jack is projected on to the table while “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” by The Beatles plays over the sound system. An enormous plate arrives bearing a single, tiny, caper berry stuffed with an anchovy and deep-fried — a one-bite distillation of fish and chips.

If the dish pokes fun at the pretension of haute cuisine, Pairet dances a fine line. “There is a danger that some people will not find it funny,” says one Ultraviolet diner, who asked not to be named. “It is supposed to be fun but then, you know, you are paying Rmb4,000 [£400]. That is more expensive than the most expensive restaurant in Manhattan.”

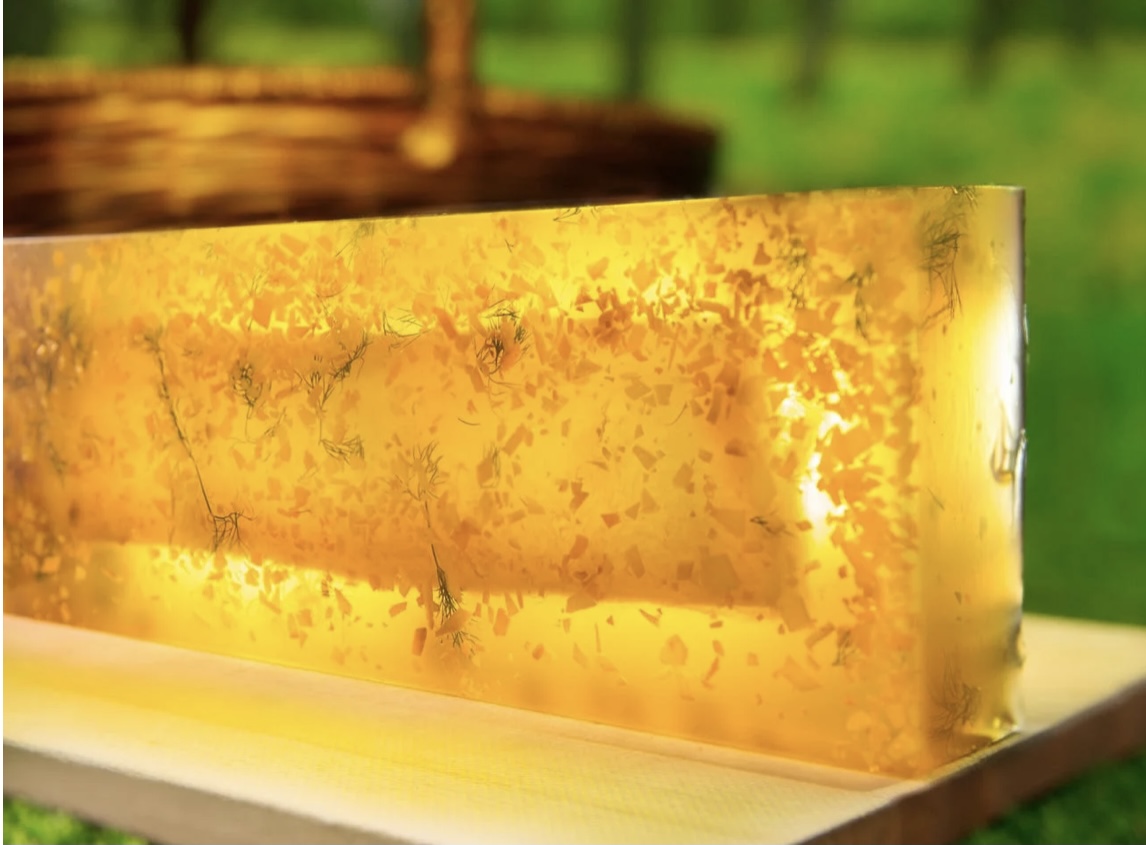

After a sequence of small dishes, diners get a break in a second room featuring the trunk of a camphor tree. Then comes a cucumber ice lolly and they return to find the room dressed for a picnic, with the scent of a field and projections of the countryside. There follows three serious courses including a rack of lamb roasted in a shell of gellan — a gum that seals in its juices. At the very end of dinner, waiters bring in what appears to be a bucket of dirty dishes. In fact, the foam is vanilla and beetroot and the residue left on the spoons is edible.

“The meal was as good as I have had in China and — outside of Noma [a restaurant in Copenhagen regularly voted the best in the world] — my meal of the year,” says Pyles.

Paul Pairet and Paco Roncero first met in around 2006, when the Spanish chef visited Shanghai and cooked at Pairet’s restaurant. “Paco is a very nice guy,” says Pairet. “He is the kind of guy you connect with straight away. And he is not a bad chef at all. You do not get two Michelin stars for being a bad chef.”

When Adam Melonas, a young Australian who had worked under Pairet in Shanghai, was looking for a berth in Europe, Pairet referred him to Roncero.

In 2008, Pairet emailed his alumnus, who was then working with Roncero, the first draft of his plan for Ultraviolet. After asking Pairet’s permission, Melonas showed the draft to Roncero. Both men were excited and Melonas emailed back asking for a reservation. Roncero visited Ultraviolet and toured its kitchen in 2013 — a year before he opened Sublimotion.

Pairet says he is not angry that Roncero mimicked his concept but he is indignant that the Spanish chef has not credited him for the idea. “I would be very open to sharing,” he says. “You can take the same characteristics and go your way. The thing that disturbed me is the way he has marketed it.”

Sublimotion’s website claims it is “an unprecedented staging . . . the first gastronomic show in the world”. Pairet emailed Roncero to ask for an explanation but received, according to him, a vague response from the Spanish chef saying he had mentioned Ultraviolet during the promotion of Sublimotion.

For his part, Roncero says he does not remember seeing Pairet’s email to Melonas, and that Sublimotion “is not a copy of Ultraviolet”; any similarities are down to “common sense” — the room has to be white to be able to project images. He adds: “Sublimotion is the evolution of Paco Roncero Taller” — his Madrid “workshop”, opened in 2010, described on its website as: “A conceptual space unique in the world in which state of the art technology and the most advanced design meet to elevate cuisine to a multi-sensory realm.”

Roncero is not the only famous Spanish chef who appears to have appropriated some of Pairet’s ideas. In 2013 the Roca brothers, whose restaurant El Celler de Can Roca in Girona, Spain holds three Michelin stars, created a one-off “epicurean opera” called El Somni (the Dream). The 12-course meal, about which a film was made in 2014, was matched by projections and music.

However, a spokesman for the Roca brothers says they had been working on El Somni since 2007. “Our feeling is that compared to our friend Paul [Pairet]’s project we are in two parallel worlds. We do not feel one is better than the other. Joan Roca has a very good friendship with him and definitely would love to visit and enjoy his performance some day.”

It was at the end of the 1990s that fine dining restaurants started to become increasingly conceptual. When British chef Heston Blumenthal served crab ice cream with risotto at the Fat Duck in Bray, Berkshire, it marked the start of a continuing experiment in how our senses, memory and expectations shape the way a dish tastes.

It was also the beginning of a movement in which haute cuisine restaurants, previously judged on how well they cooked, interpreted and refined dishes, became riotous playgrounds of new ideas.

But just as in fashion or art, culinary ideas are vulnerable to plagiarism and reproduction. To assert ownership, top chefs began making records of their creations. “Each year, Ferran Adrià would invent an entirely new menu for El Bulli [a Michelin three-star restaurant near Roses, Catalonia that closed in 2011]. At the end, he would spend a month taking photos and publish it all,” says Emilia Terragni, head of the culinary publishing division of Phaidon. “It showed all the dishes and the plating and the crockery as a record,” she adds. “It showed how the flavours had been put together. If you copy it, shame on you.”

Heston Blumenthal agrees: “Look in the Fat Duck cookbook and everything is dated and there is a chronology of who I met and worked with. It is a record of my inspiration.” He adds that the world of fine dining has “lots of people” who falsely claim to be original. “But I think if someone takes an idea and moves it on that is fantastic.”

The Fat Duck is set to reopen in October after a six-month hiatus with a new menu. In keeping with the ever more experiential trajectory of haute cuisine it promises to supercharge its dishes with a healthy dollop of nostalgia from its guests, something Blumenthal has drafted in Billy Elliot writer Lee Hall, illusionist Derren Brown and even a font specialist to help him execute.

As restaurant concepts have become ever more complicated and technology has been introduced (Blumenthal has used headphones in the past to influence how diners experience certain dishes), superficial elements — projectors, audiovisuals, the colour of the walls — can make one restaurant appear very similar to another. But just as in art, where two artists can work in the same medium yet produce unique pieces, restaurateurs keen to push the boundaries of haute cuisine can reinterpret similar ingredients with wildly different results.

That’s the ideal, at least; there have been claims about copycat restaurants before. In 2007, Rebecca Charles, the chef at Pearl Oyster Bar in New York, sued her former sous-chef, Ed McFarland, alleging he copied “each and every element” of her restaurant, including the white marble bar and the colour of its paint. The two sides eventually settled out of court and McFarland introduced new dishes to his menu.

But it is vanishingly rare to find a copy in haute cuisine, where the best restaurants are so famous that imitations are instantly detectable. In 2006, Interlude, a restaurant in Australia, was shamed on the food forum eGullet for serving dishes that appeared almost identical to those in two US restaurants, Grant Achatz’s Alinea and Wylie Dufresne’s WD-50. Interlude closed in 2008.

Amy Trubek, a food historian at the University of Vermont and author of Haute Cuisine: How the French Invented the Culinary Profession, says there has been no history of copyrights and trademarks in the business either for recipes or the performances of meals. “There is a longstanding tension in professional cooking,” she says. “Should it be understood as a craft or an art? If it is craftsmanship, imitation is a form of flattery. But if a meal is cast as an artistic performance, then questions of ownership can arise.”

Adam Melonas, 33, who has now moved on from Roncero to work in the US, agrees. “You never own the rights to a concept but ethically and emotionally I think Paul [Pairet] is a million per cent in the right.” He does, however, point to a cultural difference between the way Pairet and Roncero approach cooking.

“When I worked with Paul it was during the combative years,” says Melonas. “The world of chefs was very adversarial and we were so paranoid about other chefs taking our dishes and techniques. I used to think in the same way. I would trawl through the web to see if other people had stolen my dishes so I could call them out,” he adds.

But when he arrived in Spain to work for Roncero, he found the chefs sharing ideas, techniques and even dishes. “I was dumbfounded and I asked them whether it pissed them off when other chefs take their creations. They said no, if a chef can take something and make a living from it, why not?”

Roncero agrees: “I hope more people do Sublimotions, Ultraviolets or whatever they want to call them,” he says. “That means that the main concept works and we have come to the people. Spanish cuisine has grown and evolved and has not stuck and it is where it is because we share experiences, knowledge . . . and someone always evolves that knowledge or that concept. In this way we grow together.” After all, imitation is the sincerest form of flattery.

But for Pairet it is a matter of honesty. He quotes Ferran Adrià to underline his point: “If you want to be creative, you have to force yourself not to copy.”

Ultra violet opening times

Open from Tuesday to Saturday evening.

Booking and waiting lists open 4 months in advance.

The second most expensive restaurant in the World

A 22 course meal in 22 settings

Join our Gold and Silver investment club

Sources Business Insider, FT