In the first music video from their collaborative album, Everything Is Love, Beyoncé and Jay-Z completely take over the Louvre. Long lines, security guards, and rope barriers be damned, the Carters swagger, strut, and pose their way through the the world’s most visited museum and the world-famous high temple of European fine art.

Setting “Apeshit” in the Louvre is more than just a flex: It’s a dramatic expansion of the type of culture normally presented in this elite space, one where people of color have long felt excluded, unwelcome, and unrepresented. But the Louvre itself was first established in a similar act of radical inclusion. Originally the official residence of the French kings, the Louvre became one site of the royal art collection after Louis XIV (also known as the Sun King) moved the court to Versailles in 1682. For most of the eighteenth century, public access to art galleries was extremely limited, subject to the whims of the princes and royal societies who owned the artwork. But in 1793, on the first anniversary of the overthrow of the French monarchy and the establishment of the Republic, the Louvre was declared a state museum, property of the people and freely accessible to all, without charge — a new, democratic institution for the new age.

Much of the video’s symbolic power stems from this juxtaposition of the Carters performing in such a traditional bastion of white (male) European culture. The camera lingers over the few Black figures in the collection — the dark-skinned servants in Paolo Veronese’s Wedding Feast at Cana, the Black sailor in Théodore Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa, the nameless subject of Marie-Guillemine Benoist’s Portrait d’une Négresse(Portrait of a Negro Woman) — underscoring the overwhelming whiteness of the museum’s collection.

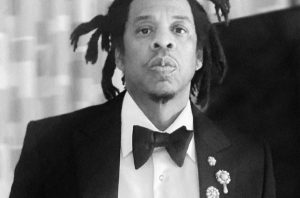

Throughout their careers, both Jay-Z and Beyoncé have repeatedly deployed royal imagery — from Jay-Z’s Watch the Throne collaboration with Kanye West to “Queen Bey’s” fashion homages to Cleopatra and Nefertiti. With “Apeshit,” they take this imagery a leap forward, literally taking over a former French palace and adding to its collection by creating their own work of art.

This royal roleplay feels especially radical when set against Jacques-Louis David’s massive 1807 work, The Coronation of Napoleon. After two hundred years of jokes about his short stature, French statesman and military leader Napoleon Bonaparte remains largely as a figure of ridicule in American culture. David’s work, commissioned by Napoleon himself, captures both the magnetism and menace of this self-made man. Born into relative obscurity, the son of a minor Corsican noble rose through the ranks of the Army during the French Revolution, winning acclaim for successfully defending the Republic against European monarchies. The painting shows how, a little more than a decade later, the onetime “Savior of the Revolution” ascended to a rank even higher than that of the kings he fought to overthrow.

Like Napoleon, Jay-Z often cast himself as the renegade outsider turned hip-hop kingmaker, a kid from the Marcy Projects who revels in the material fruits of his success. The Louvre’s hometown of Paris itself appears as a status symbol in “N***as in Paris”, his 2011 collaboration with Kanye West:

If you escaped what I escaped, you’d be in Paris getting fucked up, too.

If you’ve made it all the way from Corsica, why not have yourself made emperor?

In the painting, behind Napoleon sits Pope Pius VII, wearing the befuddled gaze of a man who’s just been rendered totally irrelevant. His very presence was a huge get for Napoleon: Not only did it demonstrate that his rule was ordained by God, but it also represented the full reconciliation of the Catholic Church and the French state after decades of open hostility during the French Revolution. And Pius’s role here, in the coronation, was to crown Napoleon. But when the moment arrived, Napoleon seized the crown of laurels from the Pope’s grasp and placed it on his own head. In one swift gesture, Napoleon upended the dynamics of the entire ceremony. The only power move bigger than getting the Pope to travel all the way from Rome to crown you emperor, is getting the Pope to travel all the way from Rome and then make him stand and watch as you crown yourself. Consider this the early nineteenth century version of being asked to perform at the Super Bowl, then bragging about turning them down, as Jay raps on “Apeshit”:

I said no to the Super Bowl: you need me, I don’t need you

Every night we in the end zone, tell the NFL we in stadiums too.

And David’s initial sketches depicted Napoleon crowning himself; you can see traces of the original figures on the canvas. In the end, however, he adjusted the scene to show Napoleon crowning his wife, the Empress Josephine. No one knows why the change was made, but many speculate that Napoleon asked for the alteration. Or in Jay’s words:

Motorcades when we came through

Presidential with the planes too

The kneeling Empress is portrayed as demure and submissive, but the real-life Josephine de Beauharnais was far more ambitious and strong-willed. Born on the Caribbean island of Martinique, Josephine employed her physical beauty and charisma to shrewdly navigate the treacherous waters of revolutionary French society. Her first husband was guillotined during the Reign of Terror, and she nearly suffered the same fate. Her relationship with Napoleon, her second husband, was notoriously tempestuous, with allegations of infidelity on both sides, and ended in divorce in 1810. But their love was passionate while it lasted — surviving love letters say as much. (They’re also rather raunchy in parts: Napoleon channels Kelly Rowland, Beyoncé’s former bandmate, in sending Josephine “a kiss on your heart, and one much lower down.”) Today, Josephine remains a source of fascination, the subject of biographies and novels that cast her as a sex-positive feminist icon.

The parallels between Napoleon and Josephine and Jay-Z and Beyoncé shouldn’t be read as historical truths. Rather, they show the extent to which history itself is packaged in the Louvre and other elite cultural institutions like it. Watching “Apeshit,” we’re inclined to see the Carters as bringing politics to the Louvre. But the Louvre is an inherently political space in its own right. Its collection advances a particular narrative of French (and by extension, Western) culture and history, one that emphasizes aesthetic sophistication, artistic refinement, and the triumph of Enlightenment reason and liberty over despotism and irrationality.

Of course, this narrative is patently self-serving. The story the Louvre tells its guests is as meticulously messaged as the details of a celebrity romance, and the moments immortalized in paintings on its walls are just as carefully chosen as the shots on any Instagram profile.

David’s painting depicts a resplendent, imperial, triumphant Napoleon at the height of his swagger — but not the Napoleon who inaugurated modern Europe’s fixation on regime change in the Middle East with his 1798 invasion of Egypt. Or the Napoleon who reestablished slavery in the French Empire in 1802, eight years after the Republic had abolished it, subjecting enslaved Blacks in the Caribbean (and the territory of Louisiana, sold to the United States the following year) to decades of further oppression and brutality.

The omissions around Josephine are even more fraught, as they relate more directly to the centrality of race in French history. Josephine wasn’t just born on Martinique; she was born into a prominent French slave-owning family, on a plantation of approximately 200 slaves. Josephine was white, but as Dr. Natasha Barnes explains in her 2006 book, Cultural Conundrums, much of her sexual appeal in France stemmed from the erotic and exotic perception of her as a woman from the colonies — a “creole”, in the phrasing of the time. In a love letter, Napoleon wrote, “Good God! How happy I should be if I could see you at your pretty toilet, little shoulder, little white breast, elastic and so above it a pretty face with a creole headscarf, good enough to eat.” The mention of Josephine’s “white breast” and her exotic “creole headscarf” (a style originally worn by female slaves before being appropriated by their white mistresses, and seen several times in the “Apeshit” video) suggests that Josephine was able to successfully incorporate elements of Black women’s culture while maintaining her white feminine respectability and status.

“Apeshit” is an emphatic, defiant celebration of Black love, Black success, and Black creativity. By taking over the Louvre, Beyoncé and Jay-Z firmly enthrone themselves as musical royalty. They also remind us that the concept of royalty has always been about presence, charisma, and marketing… and how that marketing has long served to cover up racial violence and exclusion.

In 1991, vandals “executed” a marble statue of Josephine in a public park in Martinique, cutting off her head and splashing her torso with blood. The statue has never been repaired, and still stands in its mutilated state, a visceral reminder of the violence inherent in the value systems that created white aesthetic ideals.

By Lauren A Henry

History PhD Candidate at Ohio State University studying migration, ethnicity, and race in modern France.