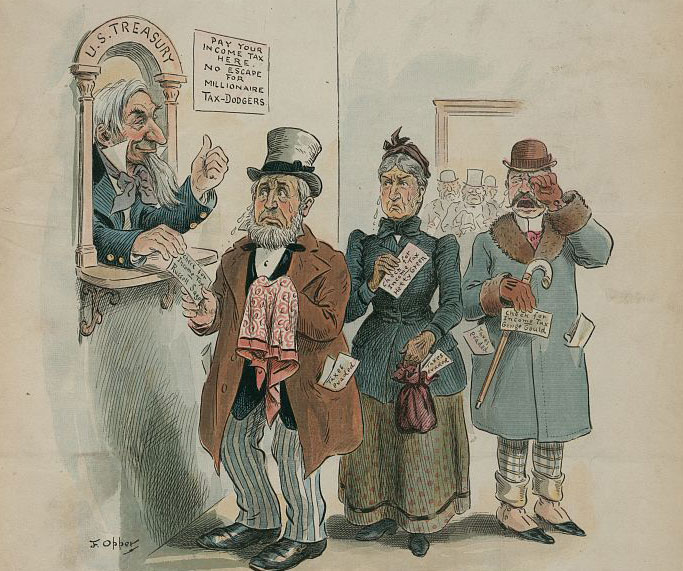

Walking the streets in black clothes and making obscene amounts of money, Hetty Green was one of the Gilded Age’s many characters.

They say that power corrupts–in the case of Henrietta “Hetty” Green, a female financier who won on Wall Street, the story is a bit more complex.

Green, who was born on this day in 1834 to a wealthy Massachusetts Quaker family, took her family’s talent for money to a new level. In her day, Green’s fortune “was linked with the likes of Russell Sage, JP Morgan, John D. Rockefeller and other financiers and tycoons of the day,” writes Ellen Terrell for the Library of Congress. But although her financial story is relatively straightforward, Green’s personal story is one of passionate fixation on money.

Before she was born, Green’s family “had made millions with their whaling fleet and shipping interests,” Terrell writes. Her grandfather, Gideon Howland, passed on that skill set to her. When she was still young, he “would talk to her about financial matters and encourage her to read financial papers,” Terrell writes.

By the time she was 13, Green had “taken over accounting for the family business,” writes Amanda Leek for The Telegraph. When she was 20, Leek writes, Green’s father bought her “a wardrobe full of the finest dresses of the season… in order to attract a wealthy suitor.” Green sold her new wardrobe and bought government bonds with the proceeds.

As this might indicate, Green had her own priorities. She “was a financier,” writes Therese ONeill for Mental Floss:

Her handwriting was sloppy and riddled with misspellings, but she surely knew her numbers. More importantly, she knew how to increase them. She oversaw tremendous real estate deals, bought and sold railroads, and made loans. She was particularly adept at prospering during the downfall of others; buying falling stocks, foreclosing properties, and even holding entire banks, entire cities, at her mercy through enormous loans. Depending who you asked, she was either a brilliant strategist or a ruthless loan shark. Collis P. Huntington, the man who built the Central Pacific Railroad and personal enemy of Hetty, called her “nothing more than a glorified pawnbroker.”

In a time when white women still weren’t even legally considered full people and were expected to align themselves with their homes and families, Green had other priorities. Like any other big financier of the day, she committed unscrupulous acts—for instance, contesting her aunt Sylvia Howland’s will using a forged signature (she lost in court). And as the sale of her new wardrobe suggests, she had limited interest in family.

Green did marry, to a man named Edward Henry Green, but their marriage included the unusual step of a pre-nup, which protected Green’s fortune. She had two children, and groomed her son Edward to take over the fortune, writes Oneill, after her husband died young.

The most memorable image of Green–and the one that earned her the sobriquet “witch”–came after the death of her husband, when she started wearing mourning clothes. And her fixation with making and maintaining money grew and grew, to the point where she wouldn’t seek medical attention for herself or her children because of the cost, and they all lived in cheap housing and moved frequently.

Through all of this, Green kept investing, primarily in government bonds and real estate. “Hetty died in 1916. With an estimated $100 million in liquid assets, and much more in land and investments that her name didn’t necessarily appear on,” writes Investopedia. “She had taken a $6 million inheritance and invested it into a fortune worth upwards of $2 billion [in today’s money], making her by far the richest woman in the world.” A big difference between her and others such as Carnegie and Rockefeller is that she wasn’t an industrialist. Her sole business was investing in real estate, stocks and bonds. That might go some way to explain why she didn’t leave a legacy of her name as her male peers did.

However, Green did make a material contribution to the field of investing, which shaped the twentieth century. She was an innovator in the field of value investing, which has made billionaires out of people such as Warren Buffett. Green was eccentric, but in her own special way, she was also a genius.

Rebellious Children

Ned and Sylvia took different paths when they received their inheritances. Sylvia, who had married a man of reasonable means late in life, made few changes. But Ned craved adoration and high living. He married his first lover, a prostitute named Mabel whom his mother had hated. Together they sought popularity and acceptance, spending money in a grand fashion to accomplish it. They built mansions, bought a private island, and kept a passel of young ingénues referred to as Ned’s “wards.” Ned even constructed the largest and most awkward yacht then known to man, and then found himself too seasick to ever use it. He indulged in the new sciences of radio, broadcasting from his own radio station at his Round Hill estate, and allowing MIT access to his equipment for study. When Ned died in 1936, he had miraculously managed to maintain a decent fortune, and left the majority to his sister, Sylvia.

And what did Sylvia do, the quiet, unattractive girl who was now one of the richest people on earth? What did she do with the money of a woman who could not abide giving anything away? She performed an act of rebellion, perhaps her only one.

She left the fortune, around $443 million* at the time of her death in 1951, entirely to charity.

Sources Smithsonian Mag, Mental Floss

Click here to become a Slaylebrity curator