It was all so painfully awkward. That night, Brittany Ashley, a lesbian stoner in red lipstick, was at Eveleigh, a popular farm-to-table spot in West Hollywood. The restaurant was hosting Buzzfeed’s Golden Globes party. For the past two years, Ashley has been one of the most visible actresses on the company’s four YouTube channels, which altogether have about 17 million subscribers. She stars in bawdy videos with titles like “How To Win The Breakup” or “Masturbation: Guys Vs. Girls,” many of which rack up millions of views.

The awkward part was that Ashley wasn’t there to celebrate with Buzzfeed. She was there to serve them. Not realizing that her handful of weekly waitressing shifts at Eveleigh paid most of her bills, a coworker from the video production site asked Ashley if her serving tray was “a bit.” It was not.

The question sent Ashley into a depressive spiral. Hers just wasn’t the breezy, glamorous life people expected from her. Customers had approached her at work before, starstruck but confused. Why would someone with 90,000 Instagram followers be serving brunch?

Simple: because Ashley needed the money. And yet, she said, “as I started having more visibility on the internet, I had to scale back on serving people.” Her wallet took the hit, and so did her pride. “My coworkers would tell me a table of kids was freaking out [about seeing me] and I’m like, ‘What? Am I going to go say hi and take a picture in my work uniform?’”

The disconnect between internet fame and financial security is hard to comprehend for both creators and fans. But it’s the crux of many mid-level web personalities’ lives. Take moderately successful YouTubers, for example. Connor Manning, an LGBT vlogger with 70,000 subscribers, was recognized six times selling memberships at the Baltimore Aquarium. Rosianna Halse Rojas, who has her own books and lifestyle channel and is also YouTube king John Green’s producing partner, has had people freak out at her TopMan register. Rachel Whitehurst, whose beauty and sexuality vlog has 160,000 subscribers, was forced to quit her job at Starbucks because fans memorized her schedule.

In other words: Many famous social media stars are too visible to have “real” jobs, but too broke not to.

Platforms like YouTube mirror the U.S. economy’s yawning wealth gap, and being a part of YouTube’s “middle class” often means grappling daily with the cognitive dissonance of a full comments section and an empty wallet. Journalists kvell over stars like Swedish gamer Pewdiepie, whose net worth is around $12 million, or comedian Jenna Marbles, who’s worth around $2.5 million. On the other extreme, fan-funding sites like Patreon (a Kickstarter-type site that allows for ongoing funding) are at the center of a communal movement to fund “smaller YouTubers.” But that definition gets blurry. Is someone with 50,000 subscribers worth supporting financially? How about 200,000? What if people assume you’re too successful to need money, and you’re too proud to tell them otherwise?

Nobody knows all this better than me. I’m 27 years old and have been building an online following for 10 years, beginning with a popular Livejournal I wrote in high school. A couple of years ago, after moving to Los Angeles, I made the transition from freelance writing to creating online video. The channel I have with my best friend Allison Raskin, Just Between Us, has more than half a million subscribers and a hungry fan base. We’re a two-person video creation machine. When we’re not producing and starring in a comedy sketch and advice show, we’re writing the episodes, dealing with business contracts and deals, and running our company Gallison, LLC, which we registered officially about a month ago.

And yet, despite this success, we’re just barely scraping by. Allison and I make money from ads that play before our videos, freelance writing and acting gigs, and brand deals on YouTube and Instagram. But it’s not enough to live, and its influx is unpredictable. Our channel exists in that YouTube no-man’s-land: Brands think we’re too small to sponsor, but fans think we’re too big for donations. I’ve never had more than a couple thousand dollars in my bank account at once. My Instagram account has 340,000 followers, but I’ve never made $340,000 in my life collectively.

The high highs and low lows leave me reeling. One week, I was stopped for photos six times while perusing comic books in downtown LA. The next week, I sat faceless in a room of 40 people vying for a menial courier job. I’ve walked a red carpet with $80 in my bank account. Popular YouTube musician Meghan Tonjes said she performed on Vidcon’s MainStage this year to screaming, crying fans without knowing whether she’d be able to afford groceries.

Every other week, Tonjes, 29, debates getting another job but wonders how she’d have the time to keep up her three channels on top of a 9-to-5. Although she has a degree in digital media, part-time social media gigs are hard to come by because the workforce is overrun by “every 12-year-old with Facebook.” Her vlog and music channels, which have amassed around 300,000 subscribers, take up more than enough hours to be her full-time job.

“This is making me sad,” she said as she took stock of her future job options at a Starbucks in Sherman Oaks. “I have to do YouTube at this point. Shit. I have to succeed.”

That means “get rich or die trying”—and not only on the internet. With American middle class jobs shrinking and wages stagnating, lots of us feel like if we don’t want to be poor, we have to make millions. These economic patterns began decades ago, and the “starving artist vs. sellout” paradigm has existed since time immemorial. Countless artists from Van Gogh to Modigliani never got to enjoy their legacy’s fame and fortune. But thankfully, Van Gogh didn’t have to shill for Audible.com to pissed-off fans of his art.

And like many other areas of the economy, YouTube has a basic supply and demand problem. Everybody wants to be there, so fledgling performers put up with a lot because they want to be famous.

“If you have a million people waiting behind you for your job”—being a social media star seems so fun, after all—“then no one has to treat you well,” said economist Jodi N. Beggs, a lecturer at Northeastern University.

She likened trying to get famous through social media to shelling out money for college—in each case, one suffers through hard work and zero-to-negative income in the hopes of a later payout. The difference, Beggs said, is that YouTube is more accessible “because there’s no admissions committee.” The technical term for this is the Dunning Kruger effect, where unskilled individuals believe themselves to be more adept than they are.

“It’s not surprising that the failure rate on YouTube would be higher because people aren’t good judges of their own abilities,” Beggs said. The result is that the market is oversaturated, and subscriber numbers, which rarely make any sense, become the gatekeepers of financial success.

It’s doubly frustrating in the YouTube economy because its workers can’t even admit that these dynamics exist. Even though it correlates with American economic trends, it plays by the social norms of the internet. Online culture has often placed emphasis on both social justice and purity—or at the very least, humility. While watching makeup tutorials by a YouTuber named Jaclyn Hill, Beggs noticed a pattern of apologizing in Hill’s videos. Every time she gets something nice, like a Valentino purse in one video, she offers caveats like “I know it’s a big splurge! Sorry!”

In other economic realms, “it’s the opposite,” Beggs said. “Rappers are bragging in music videos.” Elsewhere, the trend is to show off wealth; that would be a major faux pas on YouTube. Whereas we’re used to a CEO being a millionaire, a popular YouTuber’s “business is predicated on ‘hey, I’m just like you.’”

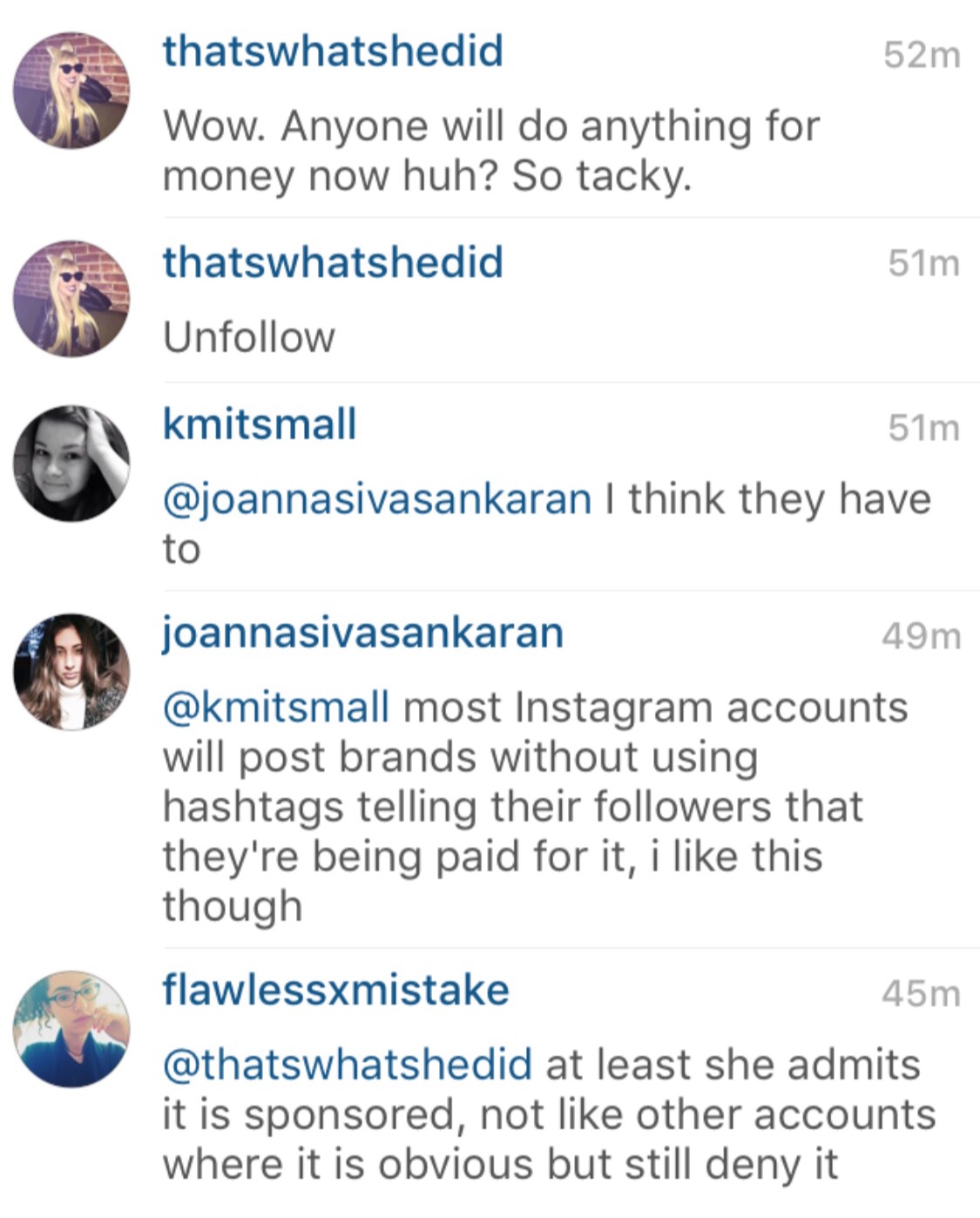

That means fans don’t want to see that you’re explicitly on the hustle. Whether they realize it or not, they dictate our every financial move. Every time Allison and I post a branded video—a YouTuber’s bread and butter—we make money but lose subscribers. A video we created for a skincare line, for instance, drew ire from fans writing “ENOUGH WITH THE PRODUCT PLACEMENT,” despite this being our third branded video ever. One dismissively chided us, “Gotta get that YouTube money, I guess” with no acknowledgment of the two years of free videos we’d released prior. Another told us they hated ads because they had “high expectations of us.”

Allison and I have turned down products for all kinds of reasons—the CEO made sexist comments; it isn’t something we’d really use, like beard oil—but it all comes down to pleasing the viewers. The con is loss of income, the pro is the trust of our fans.

Sometimes, this coveted intimacy can ding our bank accounts. In a 2013 speech, Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers Alan Krueger said the increase of knowledge about a performer’s life and beliefs due to social media has led to not being able to charge as much for concert tickets. Besides, “most people do not want to think of their favorite singer as greedy,” he said. “Would you rather listen to a singer who is committed to social causes you identify with, or one who is only in it for the money?” If an artist—a YouTuber or Instagram star, for instance—is committed to championing the little guy, they can’t very well look like they’re taking money for their work.

YouTuber Anna Akana, fed up with comments calling her a “sellout,” posted a video in Juneexplaining how without brand deals, YouTubers can’t survive. Akana has hit 1 million subscribers by creating a podcast, designing a clothing line, and yes, taking money for sponsored videos. Some fans understood and defended YouTubers needing to make money. Others vowed never to watch her again. It’s a terrifying risk whenever you post a branded video.

Some of us are able to maintain relative purity by minimizing our cost of living. Social justice vlogger Kat Blaque is one of the only people I follow on social media who talks about her real life without making it seem glamorous. Her videos have low overhead and little production value. She doesn’t own a car and lives outside LA, in a cheaper area. This is good financially but limits her ability to collaborate and grow her channel. Blaque, however, views YouTube as a platform for other opportunities, like speaking about trans issues all over the country, illustrating original merch, and making videos for sites like pride.com and Everyday Feminism. It’s symbiotic. She needs these outside gigs to keep up her channel and she needs her channel to get these gigs.

“Having subs doesn’t mean you’re Gucci all the time,” she said. “You have to reach a point where you’d be getting other opportunities.”

For the few of us who do make a middle-class income, the answer is to say “fuck it” and do as many brand deals as possible. Whitehurst said she has at least 15 different sources of income. One is the Amazon affiliates program, where she shouts out things she’s bought on Amazon and gets commission if fans buy using her code. But because it’s view-based and click-based, “it’s not a stable income,” she said. And her checks only come once a month, which leaves her waiting.

Still other YouTubers make money by relying on “rage clicks”—saying something inflammatory for the purposes of press and views. Take “Dear Fat People,” a fat-shaming tirade by YouTuber Nicole Arbour. “Dear Fat People” made so much money that Arbour posted a Snapchat counting 50 dollar bills…but she also lost some of her branded deals and got blacklisted by the tight-knit YouTube community.

Of course, for every brand that pulls out, another brand will want to buy those rage clicks. So there are plenty of vloggers who traffic in them. There are endless ways to sell your soul on YouTube. The fact is if you choose not to do any of it, you lose out.

Making YouTube videos is intensely isolating, even if you manage to keep your integrity intact. The production is a barebones affair; the community is geographically diffuse. Because of this, it feels like YouTubers talk to each other about money even less than the average worker. The humiliation of not making a living wage when fans believe you’re famous can add an extra layer of silence.

“There’s shame in admitting you’re in debt,” Rojas said. “It makes me feel like an idiot and like I’ve made bad choices.”

And yet, failing to talk about money hurts our bottom line. The most Allison and I have made combined on one deal is $6,000, and 30 percent of that went to our multichannel network, Collective Digital Studios. I’ve learned that others with fewer subscriptions make twice that. A lack of communication leads to a lack of standard pricing.

“Some companies really take advantage of that,” Rojas said. “Someone accepts $4,000 and others say $20,000 and everyone’s a bit scared of losing out.” She believes there’s flawed distribution of wealth because a small handful of creators have YouTube’s structural support— appearances on the popular page, for instance, and boosts in visibility and views. Plus, more channels are using Adsense (Google’s way of monetizing ads before videos) every year, leaving less money to go around.

Money anxiety is a deep and longtime trigger for me. I’ve almost quit Just Between Us a few times, once after spending hours hysterically crying in my parked car because I wasn’t sure how I was going to make rent. My parents couldn’t help me financially because they had their own problems. I had already sold some of my old clothing at Crossroads and Buffalo Exchange. Allison’s parents offered to lend me money, but I wasn’t comfortable taking from them. Finally I borrowed money from a very kind friend who I’ve since paid back. During that time, I had more than 70,000 Twitter followers.

I eventually confided in Allison, and she’s taken on the lion’s share of paying our film crew. One day, I’ll pay her back in full. (She jokes it’ll be when we get a TV show.) But if I weren’t sharing the channel, I wouldn’t be able to afford to keep making videos for free.

Not a hint of this psychic stress has ended up on my channel. There’s a huge amount of emotional labor inherent in being an online personality—I have to seem carefree and flawless and always surrounded by friends. I can get “real,” but I can’t bum anyone out. A picture of me out to brunch in Los Feliz will get more likes than a video of me searching for quarters in my car. Authenticity is valued, but in small doses: YouTubers are allowed to have struggled in the past tense, because overcoming makes us brave and relatable. But we can’t be struggling now or we’re labeled “whiners.”

When Essena O’Neill, an 18-year-old Instagram star, quit social media for being “fake” to much praise, I mostly felt pissed off. Easy for her to quit and renege on all her sponsorships, I thought. I figured she must have made her money already, or she’s not under contract to keep a photo up for a year no matter how many fans hate it. She must have a safety net already to be able to just stop. Whereas if I don’t keep up the charade and post this Instagram photo of a “fun autumn basket of goodies,” I’ll eat ramen for a week. All this is why I’ve been hesitant to reveal anything publicly. Frankly, I’m worried about the money I’ll lose.

So what does this mean for my future as a creator? I either have to go at it the old-fashioned way—get hired to write on a TV show or movie, go on auditions—or I have to stop making stuff for the internet. My time will be hopefully taken up with “a real job” if I can find one. (The courier people haven’t gotten back to me yet.)

Aspiring vloggers may want to think about getting business degrees, because that’s what being famous online is: It’s protecting your assets, budgeting, figuring out production costs, and rationing out money to employees—whether that’s yourself or a camera crew. The numbers on your social media accounts may never match those in your bank account. The internet may always be equated with The Future, but for most social media stars, it ends up being a stepping stone to the same old metrics of success (if you’re lucky). As YouTuber Manning told me, “YouTube is not the end game, it’s the foot in the door.”

And sometimes, that foot in the door doesn’t mean a happy ending. Comedian Grace Helbig is queen on YouTube with 2.7 million subs, the inspiration for endless think pieces about the reason for her success (uh, she’s funny?). But online fans didn’t follow her to E! for her late night show, The Grace Helbig Show. The eight episodes suffered low ratings and the show was shifted around to a terrible Friday night slot. It’s unclear if the show will return after its underwhelming performance. Meanwhile, Helbig’s low-budget vlogs continue to get tons of views. The fans don’t want her on TV. They want her in her living room.

Until my “happy ending,” the mindfuck continues. This Thanksgiving, I left my family’s dinner table to fly to New York City late Thursday night and shoot a branded video all day Friday with Allison. The pay was too good to pass up, so I used some of my earnings to finally pay Allison back for our past shoots. Our task? A man-on-the-street style video, in which we convince people to go home and spend time with their families. (The irony was not lost on us.) Just below the video reads one of the top comments, dripping with sarcasm: “This may be a long shot, but I’m thinking this video is sponsored.” Another top user was more succinct: “sellouts?”

Gaby Dunn is a writer, comedian, journalist and YouTuber living in Los Angeles. Her comedy channel with her best friend Allison Raskin can be found here

If you are totally fed up with the influencer charade on mainstream social media, click here to change your life now