In 1994 our family was living in a dilapidated shack on the edge of a corn field, not too far from a huge nuclear power plant. My mother delivered me just like my older two brothers at home, underwater, by herself, without a midwife’s or doctor’s assistance. When I was born my father got suddenly very ill and nearly died, most probably from toxins in our well water and pesticides that were sprayed over our house by the crop planes. We had no kitchen, barely any furniture, except for one mattress, one chair, one small bookshelf, a few hand-made books, three pots and two iron cast pans on a portable burner. Large ugly holes and paint spots were all over the cracked plywood. The unfinished drywalls with deep cracks were our only decorations. We often washed dishes in a utility sink in our basement that was perpetually flooded.

My mother used to walk with us in our rural community in hopes of finding friends for us, but one door after another got shut in front of us. Once she even called the whole town of three thousand people and invited them to our home, but nobody came. The neighborhood we lived was rather unwelcoming: one neighbor threatened to assault us if we did not attend his church, another tried shooting our dog, another was murdered, yet another purposefully used to burn trash next to our shack causing fires we were forced to extinguish. One day in the midst of another fire alert my mother and I fell off steep run-down stairs. To this day I have a scar on my forehead from that fall.

Since my Dad’s health began rapidly declining, my mother got us a collapsible ladder to climb, and, while we played in the same tiny room, right beside us, she started a home business without any money in order to support our family. She involved all of us in her new sales endeavor: carrying me on her back in two feet high snow she walked door to door in different subdivisions and different towns selling my favorite snack—edible algae.

Within two years the business grew, and we moved into a massive ten thousand square feet Frank Lloyd mansion in Rolla, Missouri. Some of my best memories came from those four years of living there: we swam in a huge indoor pool, rode scooters along endless corridors and fished in our small lake. We loved weaving dandelion wreaths, growing butterflies from cocoons, and chasing our gigantic Newfoundland dog across the golf course hills.

Even though our library expanded to twenty thousand books I was never drawn to read. I liked actual living experiences. And since I was growing up without any relatives, what I enjoyed the most was spending time with my family. My older brothers were my best mentors and playmates, and my parents— my best role models: they always made light out of the most challenging situations. During tough times they would laugh at themselves, perform comedy skits, draw caricatures, or just tickle each other.

As soon as my father’s health improved my mother stunned everyone by suddenly quitting the business and putting our house on the market. She wanted to spend more time with us, especially me, as I needed lots of attention and guidance. Had she not made that decision, nobody would have noticed either my first shared dreams or my artistic inclinations, and without her daily support I would never have become the artist that I am today.

We did lose our library, our house, our furniture, our new playgrounds, and we did find ourselves on the edge of bankruptcy, but we gained much more—now we had our mother educating us full time. I loved her attention: she listened to me sometimes for hours at a time about the smallest details I remembered from my spectacular dreams and visions of the future and other worlds. She was the only one who believed that what I was describing was not the fabrication of my fantasies, but my real experiences, and she meticulously recorded everything in her journal.

Just like theoretical mathematicians and quantum physicists who live with another perception of the world, a separately developed sense that most of us are oblivious to, I thought I, too, possessed yet another sense— a precise and clear blueprint of the universe. Looking back at my spiritual experiences there were many unexplained manifestations, however, no other event had impacted my family as much as a baffling phenomenon witnessed one rainy spring day by so many different people when I was five—I disappeared.

Hundreds of vehicles in our small town were stopped for inspection, and my photograph was distributed throughout all local dispatches. I was able to see exactly how many police officers, state troopers, firemen, search dogs and neighbors were looking for me because of a suspected kidnapping, however nobody could see me. That’s right. Nobody. It was as if, temporarily, I was off a radar. Undetectable. I remember splitting into a myriad fragments, hundreds upon hundreds of eyes that could see in all directions and participate in many imperative planetary and extra-planetary proceedings all at the same time. Then, after many long hours, I reappeared in the midst of numerous eye-witnesses, right by the windows in the crescent shaped corridor of our house. Neither my family, nor the officers, nor I could comprehend what had really happened, nor did we discuss it any more as it carried rather distressing and inexplicable association. The only reminder of that haunting day is the stuffed Smokey bear that the police officers gave me.

After that incidence my sketches, now in color oil pastels, were on every possible flat surface of the mansion. My mother kept on guiding me to use the paper, but the paper was just too small for me. I needed much larger spaces. She was incredibly forgiving for my destructive artistic explosions and never reprimanded me for messing up the walls, the floors, the carpets, the tables, the windows, or the clothes even during the realtors’ house showings. For some reason, I did not value my paper sketches and used to throw them in a garbage. Had my mother not persistently salvaged them, none of my earlier works would be here today.

I remember how frustrated I used to be with my learning. One time I threw my pencils on the ground and began sobbing. I refused anyone teaching me, yet I did not know how to fix my mistakes. My mother smiled, took a round pocket mirror from her pocket and handed it to me. I looked at her confused. She picked my drawing and asked me, “What do you see?”

“Mistakes,” I answered peeking through the mirror. “My brother’s left eye is smaller. And his nose… Hmm…It’s much wider than I thought. Thanks, Mama, for another pair of eyes. I can’t believe I’ve made so many mistakes!”

“Akiane, if you can SEE the mistakes you’ve made, you made them RIGHT.” My mother answered.

When I decided to invite other children to our home to draw and paint with me in order to raise money for food and art supplies I unexpectedly changed my mind. A self-imposed competition was overwhelming me, but I clearly remember my mother’s wise counsel. “A palm tree is the only tree that can survive a hurricane without breaking. It can bend down all the way to the ground. This way it strengthens its roots. Your talent, Akiane, is like this palm tree. It will be stronger if you work with other children, not against them. Even though they seem like a hurricane to you now.”

Whenever I compared myself to my older brothers’ homeschool art projects or other students’ more advanced works I became so disheartened that I did not want to continue creating art at all. “I’ll never be good as them,” I would repeat. But my mother would always bring me out of the deepest despair and doubt by motivating me again and again. “A great artist is not better than others, Akiane. A great artist makes others FEEL better… A true artist is the one who finishes to the END.”

She was right: almost everyone whom I admired eventually quit art and have pursued different interests, but my mother’s constant reassurance propelled me to finish my artistic marathons. I did not enjoy working with other children, however, I could not help but notice that I began developing faster. I believe that those small doses of competition outside my comfort zone did thrust me into a deeper artistic level. However, public art competitions and street art fair exhibits I participated in, on the contrary, never uplifted or motivated me.

When Ilia, my third brother, was born I tried a few different schools for a about year and a half. One of my teachers got frequently upset with me, because I refused coloring inside the coloring books and made my own sketches. “So you made your OWN lines? Color INSIDE the lines!” She once yelled at me. “But the lines are all wrong,” I protested.

Sure enough, I did not last long in the school setting, but I believe it was a necessary stepping stone in my first encounter with the wider world. Religious art of sculptures, reliefs and paintings in one of the parochial schools I attended greatly influenced my later attraction to legendary figures. For the first time I got to encounter the world’s view of what divinity was supposed to be, but deep down I felt that I perceived everything in a much broader and deeper sense. It appeared to me as if most people were completely ignorant of other realities, or that the realities they perceived were seen only from a very narrow angle.

My father’s lifelong dream was to move to the West, so when he found a hospitality management job we moved to Coal Creek Canyon, Colorado, seven thousand feet above the sea level. Our relocation coincided with a tragic day of 9/11. There was not a day during our ten-month-long living in the Rocky Mountains without some sort of accident or sickness in our family. The fifty-year-old shaggy dark blue carpet in the house we were renting was glued on every imaginable spot of the house, even on the walls and ceilings, which we believe was the cause of poisoning for Ilia, my baby brother, who developed deep, open eczema sores that bled every day and allergies to virtually everything he breathed, ate or touched. His toxicosis manifested through life-threatening gastro-intestinal and respiratory disorders. Each time Ilia cried, he would throw up or lose consciousness, and during the night my mother had to be constantly alert as she watched over his nocturnal asphyxia. Visits to various specialists only worsened the condition.

Around the same time my older brothers got injured; Jean Lu— his back and legs, and Delfini air-lifted to the hospital after his scalding accident. For me, personally, it was one of the lowest times in my life: I developed severe migraines, debilitating vertigo and, accidentally, got one of my fingers cut off in the door hinges. Even though I did paint a few paintings, with so much going, I no longer was inspired to create art, and my mother no longer tried to change my mind. She closely observed me, but she did not attempt to influence my decision about quitting art in any way. I honestly presumed that I would never return to drawing and painting again.

Seeing me without a creative outlet my mother encouraged my literary expression instead and would write everything down I dictated to her in three languages she had taught me. I conceived poetry and philosophy effortlessly, and it seemed that I was tapping into some bottomless literary reserves, yet I was not always successful interpreting them and never enthusiastic about editing and translating, which over time resulted in ten thick journals of backlogged drafts.

After my Dad got laid off we decided to move again, this time to Northern Idaho, the location that had been revealed in one of my visions. We continued caring for our sick Ilia, but my life changed into an unexpected direction. My mother once again started reminding me of my gifts, and before long her catchy enthusiasm revived my passion for art: my vivid visions gradually returned, and so did my dedication to art: I started getting up earlier and earlier in the morning to paint, working on larger and larger canvases, and with more and more diverse mediums.

I asked my mother to take me to the farms to sketch animals and to the stores to find human models. I remember after my first oil painting my mother gave me a big hug and declared, “Akiane, this is a masterpiece. If you do nothing more in your life, you’ve already left a legacy!” Her support was more than what I could ask for, and she gave everything she had not only to me, but to all her children and to all the people around her. She never asked anything in return.

Yet despite my mother’s complete acceptance and backing, there was one distressing predicament. She was the only one who appreciated my work. There was absolutely nobody else who recognized my budding talent. And when my mother suggested showing my art to others there was an overwhelming protest from the rest of my family. On one hand, they wholeheartedly wanted to protect me from the public eye, but, on the other hand, they could not see anything remarkable in my paintings.

After months of heated tension and negotiations my mother and I invited local people to our house just to see their response, but what we encountered was a complete indifference and cynicism. Nobody seemed to like my art. A few visitors suggested even burning all my paintings and writings. My mother did not give up. She continued bringing more and more art fans, more and more art experts, but time and again, they all saw the same: nothing out of the ordinary. My mother continued writing letters to various sponsors, organizations, agents and media in hopes that someone could see what she did. But no one shared her excitement.

Realizing that nobody, except for my mother, cherished my work, I became more and more disillusioned. One time I threw my painting in the rain outside. And as it was landing into the puddle someone caught it. Just in time. It was my mother. Out of breath she shared something, “Last night I had a strange dream. I saw thousands of people waiting for your art. The line stretched all the way to the horizon.” I wanted to believe her, to believe in my own insights of the future and to believe that I could paint something inspirational, but I was becoming more and more discouraged by apathetic and malicious reactions from virtually everyone around me.

Just when I couldn’t be more disenchanted with the future of my art, one man, a self-proclaimed prodigy expert, showed up in our lives who wanted to buy my first paintings and represent me. After being enticed into signing the contract, not a day passed that he did not ridicule my family. The new agent blatantly starting taking advantage of our trust, manipulating us in the most revolting ways and even stealing my paintings.

But my mother did not give up. She kept on showering me with compliments and affection and encouraged me to persevere, to paint and to ignore all the skeptics. So spending the last savings we had on paints I tried painting again. Half-heartedly. Hesitantly. Gradually. One painting at a time. There was nobody else who was waiting for my new brushstrokes or my new visions, except for my universe and my mother, so I practiced and worked without any expectations, without any need for approval or recognition, and without any knowing what was next. I began noticing ordinary life in an extraordinary world, and extraordinary life in an ordinary world.

The more I painted, the more I felt that art was my true mission, and the more I felt the urgency to separate from the agent. In a short time, we got to face our most extreme and our most expensive challenge: ending the nine-year-long binding contract at the court mediation.

Remarkably, upon the separation from the con-artist, I received an unexpected invitation to fly to Chicago. To be a guest at the Oprah show. In a flash, my world changed, and everyone including my family and my acquaintances suddenly saw what my mother had seen all along. It was as if someone dissipated the fog and unveiled the scene to be discernible more clearly.

Shortly after, I was observing an endless line in a museum. Around two thousand people were waiting to see art. It took me a while to comprehend that they all came to see MY art. And it was also the day I grasped the meaning of vision, love and perseverance, appreciating my mother as my main compass navigating me throughout all the tumultuous storms of my intense art voyage.

Over my teenage years after my fourth brother was born we circled the world together through thirty countries and living in three continents, embarking upon reaching out to others who also needed guidance and inspiration. We counseled families about arts, relationships, cultures, ingenuity, and holistic education. We collaborated in harmonizing diverse secular and spiritual groups for peaceful communication and conflict resolution and visited hundreds of schools around the globe.

Our ideas helped many organizations and families shake off mediocrity and maximize their unlimited potential, and, in some cases, our insights caused tidal waves of immense pedagogical changes. One of the most significant heart projects of ours became global unity through literary, film, performing and fine arts and helping other aspiring and established artists, young and old, from all over the world to reach their dreams, because in order for our dreams to come true just one person is needed. Just one person who can believe and support our gifts and our mission. Just as it happened to me.

Documentary

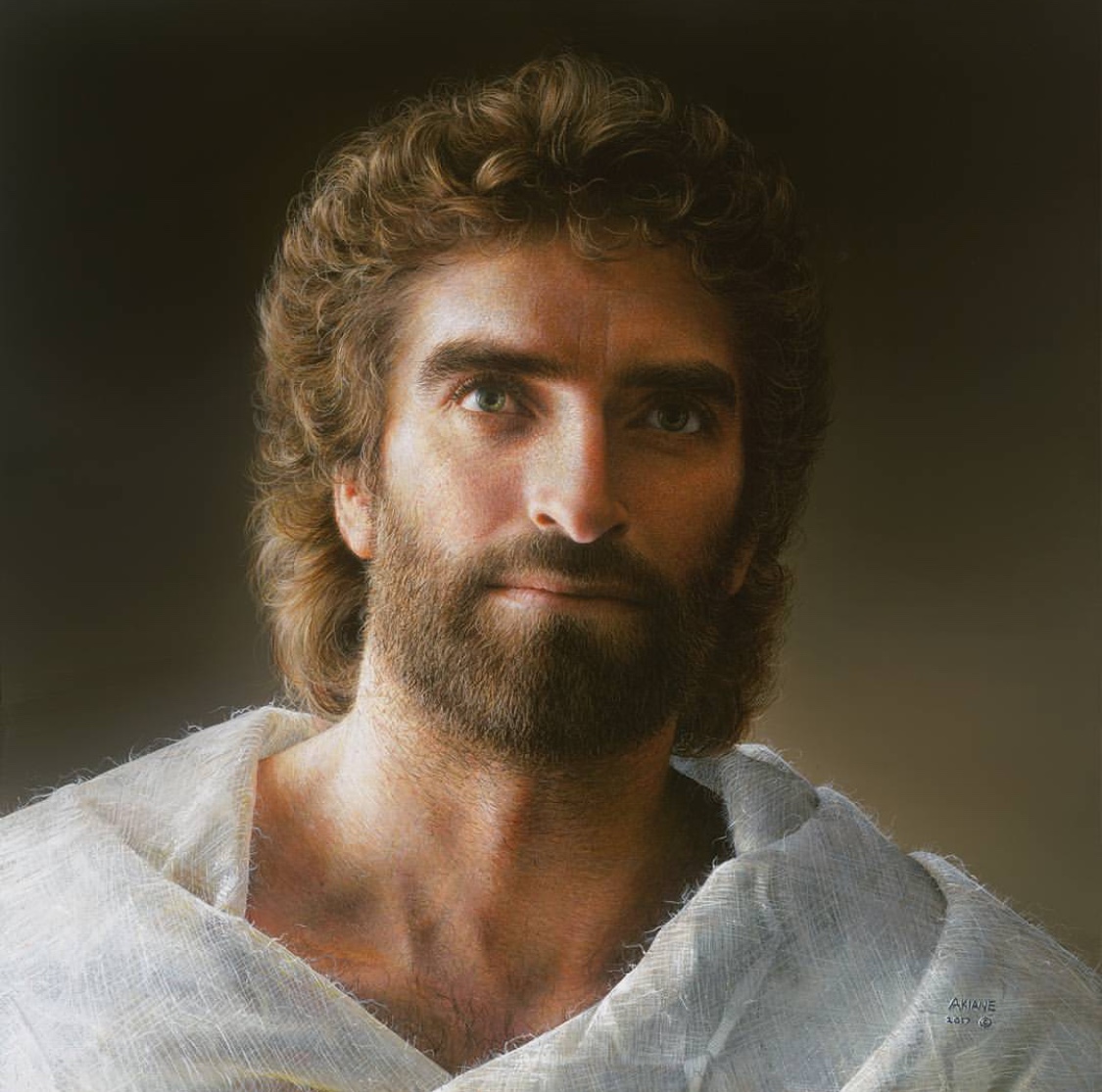

Nobody was supposed to see this painting