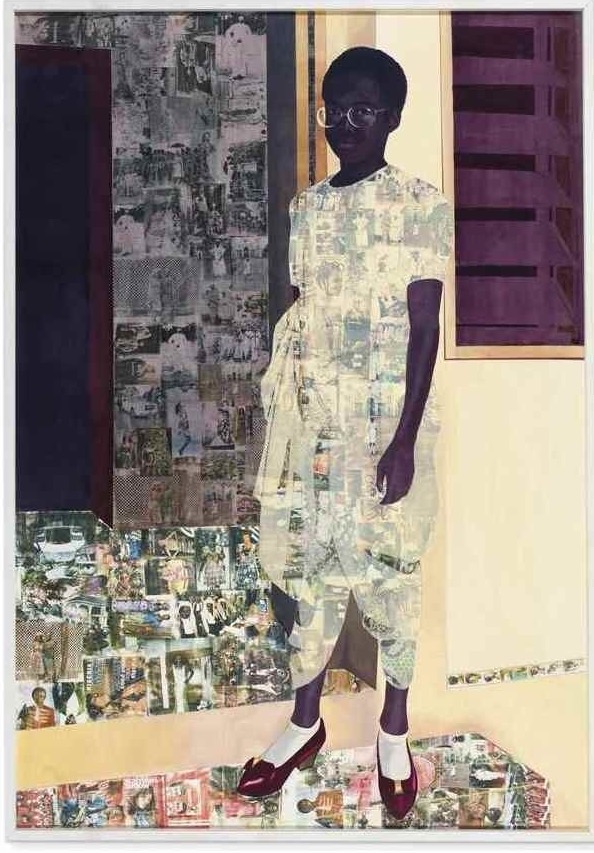

ONLY THREE WORKS by Njideka Akunyili Crosby have come to auction and they have all been record breakers. In the span of six months, sales for the Los Angeles-based artist have soared from less than $100,000 to more than $3 million. The latest high mark was achieved March 7 at Christie’s London when “The Beautyful Ones” sold for $3,075,774 (including fees).

Depicting the artist’s older sister, “The Beautyful Ones” is a standing portrait of a lone female figure. Akunyili Crosby made the mixed-media painting in 2012 during her residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem. The first and largest work in an ongoing series, it is rife with personal significance and national symbolism for the Nigeria-born artist. The lot sold for more than four times its high estimate. The price skyrocketed when six telephone bidders vied for the painting, according to the New York Times.

Njideka Akunyili Crosby made the mixed-media painting in 2012 during her residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem. The first and largest work in an ongoing series, it is rife with personal significance and national symbolism for the Nigeria-born artist.

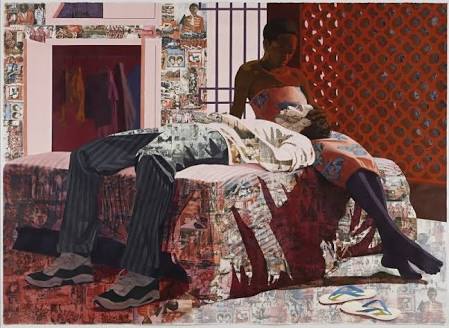

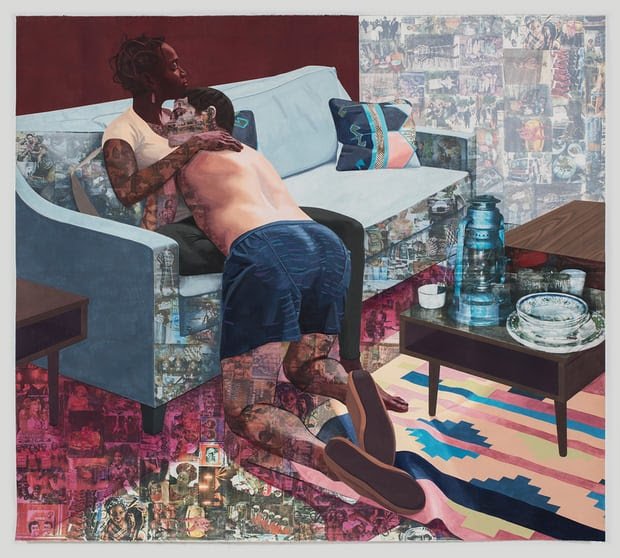

Akunyili Crosby’s impressive run began Sept. 29, 2016, when an untitled 2011 work sold at the Sotheby’s New York Contemporary Curated sale for nearly $100,000, including fees. In November, “Drown,” an image of the artist reclining in an intimate embrace with her husband, surpassed the previous level, yielding 10 times the price (nearly $1.1 million). Finally, “The Beautyful Ones” sold for a whopping $3.1 million earlier this week.

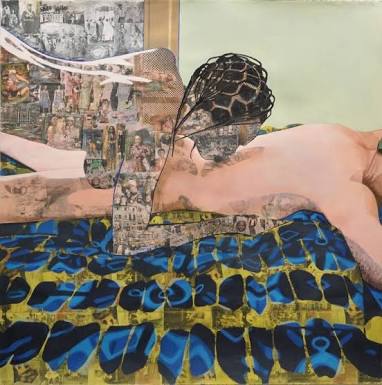

RECOGNIZED FOR HER MIXED-MEDIA collage paintings, Akunyili Crosby’s practice bridges her personal narrative with the broader political history of Nigeria. In domestic scenes and environmental portraits, she layers images from Nigerian fashion and lifestyle magazines creating works that reflect her experiences at home and abroad, challenge conventions of representation, and foreground West African figures and social and cultural issues.

After attending Swarthmore College, the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and Yale where she earned an MFA, the past few years have been career-transforming. Akunyili Crosby was awarded the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s James Dicke Contemporary Art Prize in 2014, the same day Victoria Miro Gallery in London announced its representation of the artist.

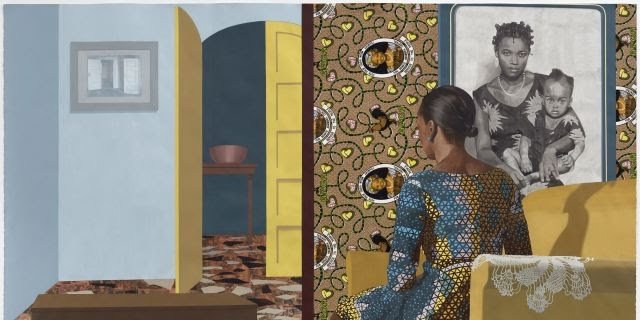

In 2015, the Studio Museum in Harlem honored her with its Wein Prize. Also that year, her first solo exhibitions in her hometown of Los Angeles were on view concurrently at Art + Practice and the Hammer Museum. The exhibition at Art + Practice, the nonprofit co-founded by artist Mark Bradford, was titled “The Beautyful Ones.” “I Refuse to be Invisible,” Akunyili Crosby’s first survey was presented at the Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach, Fla., in 2016. Both exhibitions featured “The Beautyful Ones” Series #1, a 2014/15 work similar to the $3.1 million painting, but with a blue ground.

IN THE “I REFUSE TO BE INVISIBLE” exhibition catalog, curator Cheryl Brutvan conducts an interview with the artist. During the conversation, Akunyili Crosby talks about the The Beautyful Ones series and explains how she came up with the name.

She said, “That series is slowly turning into a family portrait. The girl in the glasses is my parents’ first child, my sister, when she was younger.” She mentions paintings of her brother, the second born, and another sister, the third born.

“The Beautyful Ones” Series #3 (2014) features a boy and a girl, strangers to the artist. When Akunyili Crosby goes home to Nigeria, she takes countless photos and the images inspire her work. She saw the young pair at a family friend’s Christmas party and something about them resonated with her. “The one with the two kids is the first time I’ve done a piece with people I don’t know at all or have no connection to. Usually it’s family—a lot of Justin, my husband—and extended family depicted in my work,” she said.

“That series is slowly turning into a family portrait. The girl in the glasses is my parents’ first child, my sister, when she was younger. The one with the two kids is the first time I’ve done a piece with people I don’t know at all or have no connection to. Usually it’s family…” — Njideka Akunyili Crosby

THE NAME OF THE SERIES comes from a book about the promise of an independent West Africa. Akunyili Crosby explained the symbolism:

* “There is a book that was very popular, read in all the high schools—not just in Nigeria but probably Ghana as well, because it’s a Ghanaian book. The title is ‘The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born,’ and it was a big part of the oeuvre of Nigerian literature. It was written by a Ghanaian guy, Ayi Kwei Armah, in the ’70s.

“In the ’60s in West AFrica there was this wave of independence. Nigeria became independent in 1960, and I think it was a promising time—hopeful is the word—so lots of people had hope: meaning, ‘OK, now we’re on our own, we’re reaady to show people what we can do, things will be great and fantastic.” The decade went by and, sadly, none of that happened. There was rampant corruption; countries were going downhill instead of getting better.

“This book was written during this time, really lamenting the lost hope of that generation, how things didn’t work out. That’s ‘The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born.’

“With the Beautyful Ones series, it was coincidence that it ended up being most of my family members. I was thinking, “If the Beautyful Ones were not yet born in the ’60s and ’70s—slightly after my parents’ generation—hopefully they are in my generation.” Fingers crossed. So that’s why these are the Beautyful Ones. It’s a play that hopefully Africans who know the book will pick up on.” CT

About Njideka Crosby

Njideka Akunyili-Crosby, daughter of late NAFDAC Chairman and former Minister of Information, Dora Akunyili, has one child with American husband Justin Crosby.

In an interview with the Guardian UK, the Victoria Miro artist talked about impending motherhood, how she took her first art class at 16, her mother, Mean Girls at Yale University, her heroine Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, and the debt she owes Harlem’s Studio Museum.

She made an interesting revelation about her late mother. Akunyili, then a poor lecturer at the University of Nigeria Nsukka, was diagnosed as needing major surgery and was given 12, 000 from a work insurance fund to go to London and have treatment. But the London doctor said it was a misdiagnosis, so she gave the money back.

“Nigeria is not a country where anybody ever asks for you receipts” she explains. “And knowing how poor we were at the time, it’s amazing that she didn’t keep it”

Born in 1983 in Enugu, Njideka is seven months pregnant with her first baby, though you would barely notice.

“People in LA say, ‘what’s your birth plan’, and I’m like, ‘I don’t know!’ My whole mind has just been on this show,” she says, her laughter resonating around the vast white room. She adds that, being from Nigeria, the whole fuss around pregnancy in California seems a little unnecessary. I’m from the village,” she says, wryly, “and women there seem to give birth just fine without all this stuff.”

She moved to the US at the age of 16, and discovered that her homeland didn’t really matter to the outside world, other than as the scene of crises.

“I don’t want to write off the horrible things that happen in various African countries, but we’re not all walking around thinking about Aids and Boko Haram all the time. Those things affect us, but lots of times our problems are the silly daily problems that you have here. How do I get a date? Will my pay cheque be enough for this dress I want to wear to the wedding?”

Njideka revealed she met her heroine, acclaimed Nigerian author, who also moved from Nigeria to the US to study, a couple of times.

“She has this short story where the main character goes to a writing workshop, and she writes about someone whose boss is sexually harrassing her. And the teacher says to her, ‘Why don’t you write about an authentic African experience?’ Well, what is authentic – you think we don’t have these issues in Nigeria, too? Stuck in traffic, 30 minutes late for a meeting – that is the bulk of life. It’s a horrible example, but even in the midst of a tragedy like the Ebola epidemic – most people are probably just living their lives. That’s why so many of my figures [in the paintings] are really doing nothing. I think people sensationalize places in their heads, so I wanted to show just how normal life is in Nigeria”

Sources blue news, culture type