In August 2008, Lupita Nyong’o boarded a plane for her native Kenya. She was distraught. Five years after moving to America to become an undergraduate at Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts — an experience she had endured rather than enjoyed — and weeks after leaving a nine-to-five office job that had left her feeling stifled and trapped, her dreams were crumbling. She was 25 years old and lost.

At home in Nairobi, where she’d lived since her family returned from political exile in the mid-’80s, she confided in her mother, her rock. Dorothy Nyong’o, then the head of her own PR company (and now the managing director of the Africa Cancer Foundation), suggested she read a book: Glen Allen McQuirk’s Map for Life, a self-help tome written by a family friend.

By the end of that year, with the help of the book and her own resolve, Nyong’o had found a new objective, as improbable as her half-Mexican, half-Kenyan name. She scribbled down words she had never dared utter out loud: “I want to be an actor.”

It was an astonishing leap for an East African woman embarking on a career in which she would be hindered by her accent, her skin color and even (for a newcomer) her relatively advanced age. But nearly a decade later, Nyong’o, 34, is the most famous African actress in the world, an Academy Award winner for her mesmerizing U.S. feature debut in 2013’s 12 Years a Slave. She’s hurdled past what she calls the “Oscar curse” and the terrors that inevitably followed it. “The fear of failure was just as high as the high of success,” she notes, “because I could fall, and I could fall far.”

She’s a global star who has appeared in two Disney franchises (Star Wars and the new Marvel adaptation of Black Panther, which opens Feb. 16); she’s a brand name in films from Queen of Katwe to The Jungle Book, a fashion icon whose image has appeared on four Vogue covers (the first black actress to do so), and who has a lucrative deal with Lancome — an ironic twist for a woman who acknowledges that, deep down, “There is a part of me that will always feel unattractive.”

Sitting with her over a long coffee (in her case, mint tea) on a bitingly cold mid-January day in New York’s Society Cafe, that notion seems absurd. One is taken by her natural poise, in her sleeveless cream dress, seashells decorating her braided hair. But it’s her strength that’s more striking. She’s steely willed and outspoken, as was evidenced by her much-discussed Oct. 19 opinion piece in The New York Times about her encounters with Harvey Weinstein.

After recalling how the mogul invited her to a screening at his home, only to lead her into his bedroom and attempt to give her a massage, she described his words when they met again at a Tribeca restaurant. “Let’s cut to the chase,” he said. “I have a private room upstairs where we can have the rest of our meal.” Nyong’o declined. “With all due respect,” she replied, “I would not be able to sleep at night if I did what you are asking.” She vowed never to work with him again.

Today, she won’t go into the specifics of their dealings, but she’s forthright about the moral compulsion that led to the article. “I felt uncomfortable in my silence, and I wanted to liberate myself from it and contribute to the discussion,” she says. “That was just what I felt I needed to do, quite viscerally. I couldn’t sleep. I needed to get it out.” Over several days, she wrote and wrote, alone with her computer, then showed what she had crafted to her mother. “I had to talk to her about it because it was something that we hadn’t talked about,” she continues. “She was really moved and very supportive.”

Now the actress is planning to take an active role in the Time’s Up anti-harassment initiative and is weighing how she can best serve it. She’s as vocal in its defense as she is on subjects from colonialism to colorism, the prejudice against dark skin that is the subject of a new children’s book she’s writing, Sulwe, which Simon & Schuster will publish next year. “Sulwe is a young Kenyan girl who, though her name means star [in Luo], her skin is the color of midnight,” she says. “And she’s uncomfortable because she’s the darkest in her family and goes about trying to change that, then she has this adventure that leads her to accept herself.” The book came out of a 2013 speech Nyong’o gave “about my journey to accepting myself and seeing beauty in my complexion.”

As to her lingering doubts about her appearance: “That’s OK,” she says, with a sly smile, “because it will keep me grounded. I don’t need to be so full of myself that I feel I am without flaw. I can feel beautiful and imperfect at the same time. I have a healthy relationship with my aesthetic insecurities.”

Given her candor, one suspects Nyong’o would be equally frank about politics, if it weren’t for the danger to others. Her father, Peter Anyang’ Nyong’o, is a prominent politician in Kenya and a leader in the opposition to its current president, Uhuru Kenyatta. “I am very emotional about politics,” says his daughter after some hesitation, “in a way that makes it hard for me to articulate things in a rational fashion.”

She knows that any words she utters will be put through the echo mill back home, which has recently been torn apart by a battle between competing presidential candidates and where her comments on behalf of her father’s gubernatorial candidacy recently led to a backlash from his opponents. “She understands how politics works and how communities work,” says Mira Nair, a longtime friend of the Nyong’os who directed her in Queen of Katwe. “It’s part and parcel of her life.”

Asked whether she is political, Nyong’o says: “I don’t know. I had to share my father with politics for so long.” She laughs. “I don’t ever want to be president — let’s just get that out of the way.”

It’s impossible to understand Nyong’o and her choices — including Black Panther — without understanding her origins. Peter Nyong’o, a member of the Luo tribe and longtime dissident, is now at the pinnacle of Kenya’s political pyramid, but the road there has been painful for him and his family.

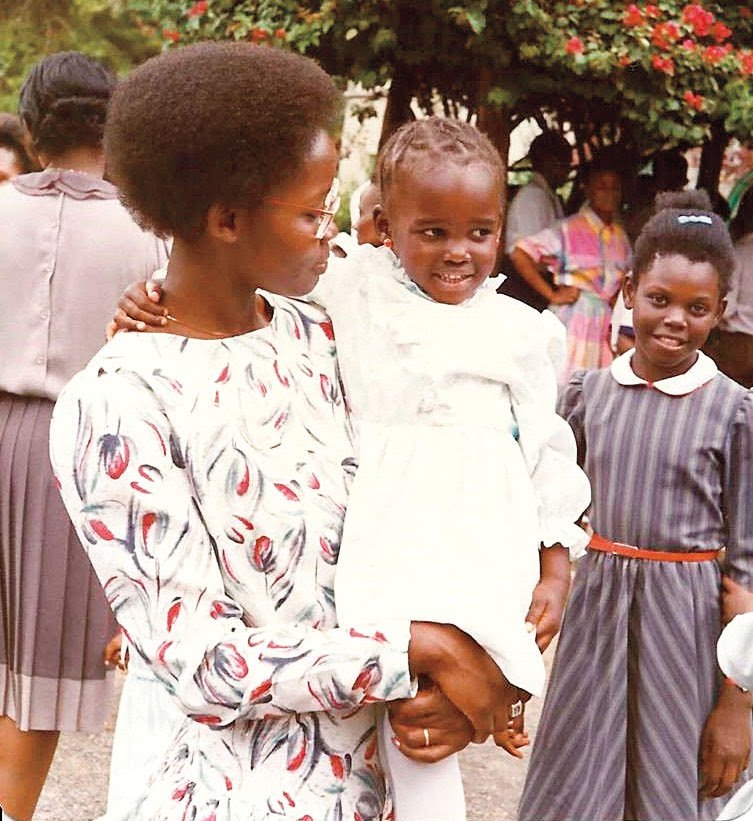

An intellectual who taught political science at the University of Nairobi, he was vehemently opposed to the authoritarian regime of Daniel arap Moi (president from 1978 to 2002), as was his brother, Charles Nyong’o. When Charles was murdered in 1980 — thrown off a ferry by thugs who were never identified — it sent a clear message. In 1981, Peter fled to Mexico, where he was joined the following year by his family as he taught political science in Mexico City. It was there that Lupita was born on March 1, 1983, the second of six siblings, and given her distinctive first name, a diminutive of Guadalupe.

While Dorothy Nyong’o returned to Kenya with her children shortly after Lupita’s birth, Peter remained in exile (he worked briefly at the United Nations, then taught in Ethiopia) and did not rejoin his family until 1987, when his continued stance against Moi led to his detention on multiple occasions. “He’s a political animal,” says Dorothy. “He wanted change in the country, and I guess some people just have to take the risk to do what it takes to bring about the change. It wasn’t easy.”

Nyong’o has only a vague memory of that time while recognizing its impact on her family and — inevitably — herself. Her father believes this instability helped create her “chameleon” qualities; but, says Lupita, “when I was growing up, I wasn’t aware of it. My parents wouldn’t tell us what was going on when he was being jailed. They protected us from that — obviously for our own good, to try to keep a semblance of normalcy in a very abnormal situation, but also to ensure that we were not at risk. The more we knew, the more danger we would be in.”

She and her siblings often were kept home and not allowed to go to school, their mother fearing what might happen if they did. “I remember staying at home with the curtains drawn,” says Nyong’o. “And my father [who was detained] had all these papers he had written, and we were burning them. I was 4.”

In prison, Peter was psychologically tortured. “They had these vaults they put people in with absolutely no daylight,” says Nyong’o. “But I didn’t really become aware of that whole period until the Moi regime was over and the torture chambers were opened, and I happened to go with my father to view them. I was 20-something, and that’s when I learned the story, with everyone else.”

It was her father’s academic connections rather than his political ones that led Nyong’o to Hampshire College, where several of his former colleagues worked.

“It was culturally shocking and culturally discombobulating,” she admits. At the university, “I was regarded with a fascination that was weird: I had grown up watching Americans on TV, so they were not as unfamiliar to me as I was to them, and that was something I had to negotiate. Hampshire can be very casual, and I was the kind of student that ironed my clothes the night before. But it was also a very liberating place because I learned that I was self-sufficient and self-driven, that I could set goals without someone flogging me.”

After graduation, she found a clerical job in New York, assisting in the creation of a coffee-table book. Her employer offered to sponsor a long-term work permit, but Nyong’o couldn’t bear life behind a desk. “New York is not a forgiving place,” she says. “I didn’t feel equipped to pursue the acting thing, and I certainly didn’t have the [visa] to do it. And so I decided: You know what? I need to go back home, where I have my community, I have a roof over my head, I have my parents, and figure out what my next chapter is.”

That Christmas, consumed with the book her mother gave her and her own conflicted thoughts and swirling emotions, Nyong’o joined her family on a vacation in Kenya’s Tsavo National Park. “It was so quiet,” she recalls. “There was no cellphone service, just this beautiful place where the elephants come, where there’s a watering hole and all the animals would drink from it at different times of the day.” Here, in the serenity of nature, looking back on her forays in the theater as Juliet in a Nairobi production of Romeo and Juliet and as the title role in a Hampshire staging of Suzan-Lori Parks’ Venus, she wrote the words she had been afraid to utter, that she wanted to act. “I said it to my mother,” she recalls, “and she said, ‘I know.’ ”

Five years later, not long after graduating from Yale Drama School, Nyong’o won the Oscar.

It was during the awards-season run of 12 Years a Slave that she met Black Pantherdirector Ryan Coogler, who was on the circuit with Fruitvale Station. Later, she says, while she was appearing on Broadway in Eclipsed, “Marvel called and said that Ryan was interested in me for a role in Panther, and I talked to him about it, and obviously everything was hush-hush, but he walked me through his initial ideas, and I thought, ‘Wait a minute? This is a Marvel movie?’ ”

It was the political themes implicit in Pantherthat drew her to that big franchise, the first comic book adaptation to feature a largely black cast. In it, Nyong’o plays the warrior Nakia, “a rebel but a loyalist at the same time,” she says. “She wants to go her own way but also wants to serve her nation.” The film centers on “what it means to be from a place and welcome others into it. T’Challa [Chadwick Boseman] is the leader of an isolated nation that has managed to keep its autonomy and be self-determining because it has shielded itself from colonization, and how does that nation now relate with the rest of the world?”

Nyong’o agreed to make Panther without seeing the script, which she didn’t read until shooting began. Then she gave it her all, marking every page with notes in as many colors as her celebrated outfits.

“She’s an incredibly serious actress,” says Coogler. “She does a lot of homework, asks a lot of hard questions. At the same time, she’s got an incredible sense of humor. She’d poke fun at me a lot. On one of our last days, she and [co-star] Letitia Wright got the crew T-shirts with all the things I said collected on the back.”

Playing Nakia meant learning to speak with the same accent Boseman had adopted, mastering the complexity of clicking sounds. “There’s three different clicks, like three different letters,” she says. The role necessitated an intense, six-week boot camp before shooting commenced in Atlanta in January 2017. “It started off four hours a day, then it was reduced to two when I started bulking up — I remember coming home for Christmas and I couldn’t fit into my clothes,” she recalls. “We would have warm-ups together, then break off and do our individual techniques. Nakia is a street fighter, so I had jujitsu and capoeira and ring blades.”

Though her daily exercise regime is now more focused on stretching and cardio, including interval training and boxing, Nyong’o says, “I have dabbled in martial arts all my life, since I was 7, maybe — tae kwon do, capoeira, Muay Thai. It’s always been an interest because in martial arts there is a mind/body relationship. You can’t do it right if you’re angry; how you can exert your power with a clear mind really interests me.”

But on the first day of shooting, the actress injured herself. She laughs. “I was fighting some bad guys, and it involved doing this scissor move. So I jumped up, and my legs went out and grabbed his waist, but I ended up spraining my MCL [medial collateral ligament]. I had to wear a brace for two weeks. Luckily, the next fight scene I had was two weeks later. I got hurt on schedule.”

Still, the pain was worth it, she says, aware of how important it is for a black superhero movie to succeed. “We were creating an aspirational world where an African people are in charge of their own destiny,” she notes. “And that really appealed to me and had the little girl inside me jumping for joy. To just have African people, black people, at the center of that narrative is so exciting.”

Fame has not been without its challenges. Immediately after winning the Oscar, Nyong’o had to leave her tiny Brooklyn apartment for a safer place. “I lived in a very unsecure neighborhood,” she explains. “I needed to move really quickly.”

She’s had to deal with the microscopic attention paid to anyone connected with Star Wars, which came her way when she was called out of the blue by J.J. Abrams while on a Moroccan vacation in May 2014. The director wanted to know whether she’d voice the character of Maz Kanata in The Force Awakens (and later The Last Jedi). The next day, she recalls, “an assistant was flown to my hotel, with a script in a locked contraption. It looked like something out of Star Wars. And he made me sign something and gave me instructions. I had a certain number of hours to read the script, and the assistant was just waiting, waiting in Morocco for me to finish reading so that he could put it in that locked thing and take it back.” She may reprise her role as Maz in Star Wars: Episode IX. “I don’t know yet,” she says. “I’ll know soon.”

That, like much else in her future, remains unclear. For a woman who confesses to liking structure — perhaps needing it, indeed — she has learned to live with mystery, uncertainty and doubt, even to embrace them. Though several projects loom, none is locked, yet she doesn’t seem perturbed. Always, she remembers that alternative: the nine-to-five life against which she rebelled.

She recently completed an independent Australian film, Little Monsters. She’d like to return to the stage but hasn’t yet committed to a new vehicle. And she’s starting to produce as well as act, with several projects in the works, including a miniseries based on Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s award-winning novel Americanah, about a young woman who leaves then-military-led Nigeria for America. She’ll also star in the adaptation.

At some point, she also wants to have a family, though she’s coy about whether she’s dating anyone. (“They make you ask that, huh?” she asks, amused. She’s been linked to GQ Style fashion editor Mobolaji Dawodu, among others.) She’s passionate about having kids. “I feel I was born to be a mother,” she says, though where she would raise her children, she doesn’t know. “Somewhere where there’s grass. Because I want my kids to be able to run around and discover things with their feet and their hands. I still love climbing trees. There’s no trees to climb here.”

For a moment, she seems wistful, recalling one of her favorite childhood memories, when she would climb the mango tree in her grandmother’s garden.

Three decades have passed since then, and they’ve taken her an unimaginable distance. She’s “a child of the world” now, as her mother says, removed from Kenya, which she hasn’t visited for two years. Perhaps one day she’ll return permanently, even follow in her father’s footsteps — not directly into politics but by embracing a larger cause, like the nonprofits she supports, WildAid (elephant protection) and Mother Health International (relief to pregnant women in areas of disaster, war and poverty).

“She’s constantly seeking, not in a restless way but a focused way,” says Nair, “to do truthful and powerful things.”

Beyond Nyong’o’s charm and grace, beyond her unquestionable talent, lies a grand purpose, even if it’s one she has not yet defined. “My father raised us to stand up for what we believe in and to fight for what is right,” she says. “We were always told, ‘You need to make a difference in the world.’ I live with that insistence all the time.”