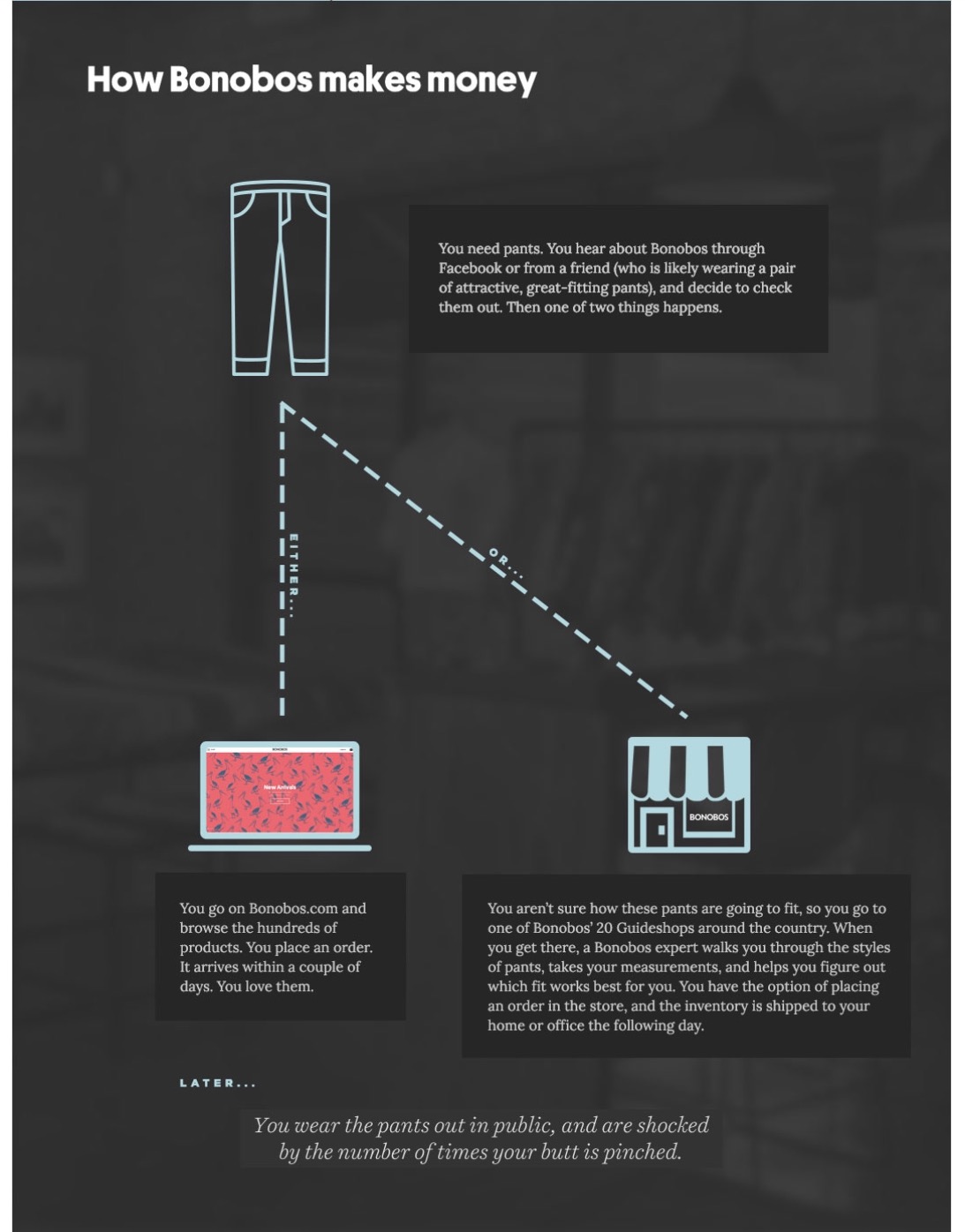

Andy Dunn is the founder of Bonobos, one of the most popular men’s clothing startups in America. Launched in 2007, Bonobos has raised $127 million in funding and is now one of the biggest men’s apparel brands in the country.

However, in the first three years of Bonobos, Andy had, on average, only $3,000 in his bank account. And even though Bonobos had $24 million in funding, at the time they were consistently only 90 days away from running out of cash.

NEW YORK, United States — “The risk not taken is more dangerous than the risk taken,” wrote Bonobos co-founder and CEO Andy Dunn, explaining his decision to turn down a secure job at a Silicon Valley venture capital firm and team up with Stanford business school classmate Brian Spaly to launch a new kind of men’s apparel brand, focused on selling well-fitting pants online. After “creative differences,” Spaly (who is now the founder and CEO of Trunk Club) left the business in 2009, in what was a mutual though difficult split. But under Dunn’s stewardship the company has not only survived, but flourished.

Dunn has succeeded in scaling the business, transforming an online-only venture selling a single product into a high-potential brand — now offering shirts, pants, sweaters and suits, both online and off — with estimated revenues of over $40 million in 2012. In doing so, he has also helped to define and prove a new model for vertically integrated fashion retail in the e-commerce era.

BoF spoke to Andy Dunn about his ambition to take Bonobos public and join the likes of Ralph Lauren, Ermenegildo Zegna and Giorgio Armani in the small club of premium menswear brands worth over $1 billion.

BoF: After Stanford business school, you turned down a job at a venture capital firm to focus on Bonobos. Why? What was the opportunity that you saw?

AD: I was inspired by my friend. I had a co-founder [Brian Spaly] who had been talking for years about how pants didn’t fit well. I remember the first time I saw the product and tried it on. The pants were like a light turquoise corduroy, with a contrast pink and blue floral liner and they just had a great fit. There was so much more joy and thoughtfulness in that product than I ever thought there could be in a pair of men’s pants.

During the first wave of e-commerce, there was some debate about whether people would buy soft goods online. And then, in 2007, there were rumours in Silicon Valley about a company called Zappos, which had been backed by Sequoia Capital and the word on the street was they were doing well and one of my mentors was like, “Hey you should take a look at what they’re doing from a customer service standpoint.”

And then it dawned on me. I had just spent a year working as a consultant on Lands’ End, and so I was aware of how that catalogue business works. And I said, wait a second, if you can build a $2 billion brand through a catalogue, you can build at least as big a brand through the Internet, because the Internet is going to be much more dynamic.

This was 2007. There were no companies on Facebook. I had never heard of Twitter. The founders of Instagram hadn’t even met each other yet.

But the belief was that by being both great at clothing and great at service, we could create a bundle that hadn’t been seen before: vertically integrated retail in the e-commerce era. And that’s what I got excited about.

BoF: How did you raise the initial funding?

How did you raise the initial funding?

AD: The very first investment in the company was Brian Spaly writing checks for $10,000 to $20,000 to buy product. I didn’t have much to my name. I cashed in a 401k the day before graduation. But soon after, I met with a man I admire a great deal, a man named Joel Peterson. He’d been a career investor and company builder and Stanford lecturer. I shared my vision with him for taking these pants and building an e-commerce experience — creating a brand that was a bundle of clothing and service. He was pretty quiet in the meeting, but when we got to the end, he said, “This reminds me of my first meeting with Dave Neeleman [founder of JetBlue Airways].” I didn’t even know at the time that he was a founding investor in JetBlue, but Joel invested $100,000. The next Monday, I went to see another mentor who I adored, Andy Rachleff, one of the co-founders of Benchmark Capital and he invested $100,000. Without these two guys Bonobos simply would not have been possible. I call them the Oracle and the Jedi, because I’ve learned so much from them, not just about company building but about life.

Between 2008 and 2009, we raised a second angel round of $3 million. And in late 2009 to 2010, we raised a third angel round which was $4 million. Both of those rounds were extremely painful. A lot of private investors believed in this, but institutional investors did not. There’s not actually great capital markets for early-stage clothing brands because the general viewpoint is that fashion sucks as a business. And so we had to educate the world about the fact that, yeah, fashion is a challenging business but e-commerce-driven fashion had some different properties, because you can access the growth of being an e-commerce company, but the margin potential of being a brand.

BoF: So how did you grow from selling a single product — pants — into a fully fledged brand that’s now selling shirts, pants, sweaters and suits?

AD: It’s funny because, today, pants are actually less than half of our business for the first time ever. But a few years ago, it was very unclear what we should do.

At the time, we did a survey of our 1,000 most enthusiastic customers. There was the usual stuff you have in a customer survey, but I only really cared about one thing: the freeform box with a 500-word limit that asked, “Why do you shop Bonobos?” I spent a weekend reading all 1,000 responses, then had an intern do a word analysis to create one of those [word clouds] and there were three things that stuck out and those became the three pillars of our brand: fit, fun and service.

BoF: Not pants

AD: Nope. Fit, fun and service. And it occurred to me that this was the opportunity. We had a chance to bring a great fit to menswear; do it with a brand, product and shopping model that was fun; and deliver a great service experience in the process. And so I said to myself, “Anywhere where we can deliver joy through fit is something we can do.” So as I started to think about shirts and even in New York, which is supposed to be a pretty fashionable place, to say nothing of the rest of America, there is a horrendous problem with having too much fabric in a shirt, so we toiled for two years to develop a standard fit shirt that was actually more flattering than what we saw elsewhere in the market.

Long story short, our shirt business next year may be bigger than our pants business. It was really my customers telling me what they wanted. Ultimately, if you use your customer as a guide, on the one hand, and you follow your instincts, on the other, you’ll be okay.

BoF: When and why did you decide to expand offline?

AD: There is a problem in being online-only, which is: it’s not a great service experience to not be able to try on clothes before you buy them, if that’s what you want to do. But the challenge is that [traditional] retail stores were not favourable for delivering great service. Growing up, I worked folding sweaters at Abercrombie & Fitch. I’ve seen that model. You’re basically the inventory manager of the store, being marginally helpful to the customers who are there. It’s more of a job about keeping clothes folded than it is about delivering service.

So we needed a new kind of store that enabled us to deliver great service. Initially, we decided to just invite customers to come to our showroom in New York and see what would happen. We installed two fitting rooms in our lobby and, literally, within a few weeks, each of these fitting rooms was a half-million dollar store from a revenue run-rate standpoint.

We then rented out a space in Boston, a tiny 500 square-foot store on the third floor of a building — you discover it mostly by appointment. And that was a very powerful store financially. All of a sudden it was like, “This is it, it’s going to be these small, service-driven experiential stores where you have one-to-one service and where we keep out the complexity of a lot of inventory, but you can access this incredibly wide assortment.

Famously, you don’t walk out with the product. And this has led some people to say, “You don’t sell in your stores.” But I have to correct them. We do, I actually sell a lot in our stores, we just don’t fulfill in our stores.

Most people in retail think the instant gratification of walking out with the product is a core part of the retail experience. It’s not. It has been astonishing how little our customer cares. In an e-commerce era, people are conditioned to receiving product through the mail. And the flip side is that, in pursuit of instant gratification, stores stock inventory and you can’t deliver something far more important than instant gratification: service.

I’m more convinced than ever that offline retail isn’t going anywhere. The focus is just shifting from distribution to experience.

BoF: Tell me about the economics of these stores.

AD: First of all, we’re finding that these stores are the best customer acquisition channel we have; the best marketing for our website. And secondly, we have amazing productivity per square foot. For the most part, we’re doing it because the model is more favourable. Our stores are from 700 to 1,200 square feet and we’ll maybe increase that to 1,500 at the top end. But we’re delivering an assortment that would normally take us at least 2,500 square feet to stock. It isn’t that Bonobos has special magic powers. It’s actually that an e-commerce showroom has more favourable trade dynamics than a traditional retail showroom does. And this is why, I think, it’s natural that we’ll see other people in our industry move towards this model. It’s just math.

BoF: How did the deal with Nordstrom come about?

AD: I started to think, “If people like to touch and try on our clothes so much, is there a partner out there who can enable more people to discover our brand? In an e-commerce world, can you think about selective wholesale as marketing?”

I met the leadership team of Nordstrom: Ken Worzel, head of corporate development, and Pete, Blake and Erik Nordstrom, the three brothers who are at the head of the company. And as I started to think about Nordstrom’s core customer, it occurred to me that their customer is older and they probably needed a customer who was younger and we could do a trade. We would help bring our younger customer there and they would help us access a customer who would probably not go online and transact as a first way of getting to know a brand. And that’s exactly what’s happened.

So my view is that wholesale isn’t going away, it’s just going to become more selective and it’s really about brand building.

BoF: Has Bonobos crossed over into profitability?

AD: Not yet. We raised a financing round at the end of last year and we’ll get to profitability on the rest of the capital that we’ve raised. If we raise capital again, prior to taking the company public, which is our aspiration, it will be elective rather than funding profitability. Having raised a total of $73 million, I’d say that the humbling thing about building a great brand is that it takes time — and that’s not different [online].

In e-commerce you can grow more quickly, but it still takes time. If you look at the people that have built great brands, with e-commerce as their only distribution channel, you see that it’s going to take you at least $50 million to get there, if you want to build a big brand. A lot of start-up entrepreneurs think, “Oh, I’ll go out and raise a $1 million to $2 million and I’m off to the races,” but that’s just the beginning. It’s not like you put up a website and just start printing cash because it’s e-commerce.

BoF: Looking back at the professional arc that you’ve traveled, building this company, what’s been the biggest challenge?

AD: That’s easy. That’s the battle with yourself. The hardest thing about being a founder is managing your own psychology. But it’s the least talked about thing.

BoF: How has that played out for you?

AD: Well, there’s this problem. Being a founder is about the act of creation, about being driven to distraction because you want to put something into the world. But being a CEO is about focus and execution and being somewhat redundant and boring in your message. In short, the human traits required to be a founder are very different to the human traits required to be a CEO. And yet the paradox is that the biggest companies are built by founders who have evolved to become CEOs, because they have the moral authority to make difficult decisions and they can never blame it on the last guy. If you’re the founding CEO, everything is your fault, which is simultaneously crippling and empowering.

In 2011, we were named the 16th Best Place to Work in the US by Crain’s New York. It was the proudest day for me in the entire history of the company, because one of the hardest things about building a business is building something your employees will love. It’s a challenge to build an environment where employees love what they do, because it’s an act of delegating control and most retail people have a hard time with that. Retail CEOs tend to be control freaks. It’s a challenge, because you do need to be a control freak in some dimensions to build a great brand, but you also need to have people who are empowered to build it.

BoF: Do you see a time in the future when Bonobos hires a professional CEO?

AD: I think building a great company is like building a cathedral. Those who are there for the start will never see its completion. So I think by definition if you want to build something truly great you have to build something that can survive you, not something that is constrained by your personality. I don’t think it will be a professional CEO though. It will be someone homegrown.

BoF: Looking into the future, where do you see Bonobos in 5 years?

AD: In the premium menswear space, there are only a handful of companies who have gotten over $1 billion. Ralph Lauren, Brooks Brothers, Hugo Boss, Ermenegildo Zegna, Giorgio Armani. The list is small. I think we have a chance to be that brand for the digital era. I see a path to half a billion of revenue in the US and half a billion globally. I don’t think we’ll be there in five years, but we’ll be on our way. There’s a lot to do to get there.

By Hustle

Sick and tired of not living your dream? upgrade Now to slay club world