J.K. Rowling’s life is a classic rags-to-riches story. Her parents never received a college education, she lived for years with government assistance as a single mother, and overcame a dozen rejections from publishers to become, almost overnight, one of the most successful and widely read authors in the history of the world.

After a couple of decades of “Harry Potter,” Rowling has turned the boy wizard into an entertainment franchise including books, movies, a play, a theme park, and more. Here’s how the author found her path to success.

J.K. Rowling — born Joanne Rowling — grew up in Gloucestershire, England, and always knew she wanted to be an author.

Rowling was constantly writing and telling stories to her younger sister, Dianne.

“Certainly the first story I ever wrote down (when I was five or six) was about a rabbit called Rabbit,” Rowling said in a 1998 interview. “He got the measles and was visited by his friends, including a giant bee called Miss Bee. And ever since Rabbit and Miss Bee, I have wanted to be a writer, though I rarely told anyone so.”

When she was nine, Rowling moved near the Forest of Dean, which figures prominently in “Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows,” and spent the rest of her childhood there.

Her parents married when they were 20, and neither attended college: Her father was an aircraft engineer at Rolls Royce and her mother was a high school science technician.

“I was convinced that the only thing I wanted to do, ever, was to write novels,” Rowling said in her 2008 Harvard University commencement speech. “However, my parents, both of whom came from impoverished backgrounds and neither of whom had been to college, took the view that my overactive imagination was an amusing personal quirk that would never pay a mortgage, or secure a pension.

Rowling had difficult years when she was younger.

Rowling never had it as bad as Harry living with the Dursleys, but she described her teenage years as being filled with difficulty.

“I wasn’t particularly happy. I think it’s a dreadful time of life,” she told the New Yorker.

When Rowling was 15, her mother was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. She died a decade later, before Rowling became a published author. Later on, one of her philanthropic projects was founding the Anne Rowling Regenerative Neurology Clinic at the University of Edinburgh with a gift of $16 million.

After graduating from college, she had a stint working for Amnesty International.

The author studied French at the University of Exeter, graduating in 1986. According to her official biography, she “read so widely outside her French and Classics syllabus that she clocked up a fine of £50 for overdue books at the University library.” Her Classics knowledge was later used when she came up with the names for spells in the “Harry Potter” series.

After graduating, Rowling worked at the research desk for Amnesty International, doing translation work. She found the work important – “I read hastily scribbled letters smuggled out of totalitarian regimes by men and women who were risking imprisonment to inform the outside world of what was happening to them,” she said – but it didn’t suit her, as she said in a later interview.

“I am one of the most disorganized people in the world and, as I later proved, the worst secretary ever,” she said. “All I ever liked about working in offices was being able to type up stories on the computer when no-one was looking. I was never paying much attention in meetings because I was usually scribbling bits of my latest stories in the margins of the pad, or choosing excellent names for the characters.”

In 1990, she began planning out the “Harry Potter” series.

On a delayed train from Manchester to London’s King’s Cross station, Rowling came up with the idea for “Harry Potter.” Over the next five years, she outlined the plots for seven books in the series, writing in longhand and amassing scraps of notes written on different papers. Separately, she also started working on an adult novel that she never finished.

The most traumatizing day of her life, Rowling said, was on New Year’s Day in 1991, when her mother died, when Rowling was 25.

“Dad called me at seven o’clock the next morning and I just knew what had happened before he spoke,” she told The Telegraph in a 2006 interview. “As I ran downstairs, I had that kind of white noise panic in my head but could not grasp the enormity of my mother having died. … Barely a day goes by when I do not think of her. There would be so much to tell her, impossibly much.”

At 26, she moved to Portugal to teach English. There, she got married, and had a daughter.

Fed up with secretary work, Rowling moved to Porto, Portugal, and taught English to students. There, she met and married Portuguese television journalist Jorge Arantes and had a child, Jessica – named after Jessica Mitford, one of her favorite authors – in July 1993. (Rowling previously had a miscarriage, in 1992, according to The Scotsman.) By November of 1993, the couple had separated.

In Porto, Rowling started a “book [that] was about a boy who found out he was a wizard and was sent off to wizard school.” When she moved back to Britain, at the end of 1993, she had “half a suitcase was full of papers covered with stories about Harry Potter.”

She lived in a small flat while going to cafes to write “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone.”

Without a job, Rowling visited different Edinburgh cafés and hunkered down to write her first novel on a typewriter. She often brought along Jessica, who slept in a pram next to her.

During that period, Rowling lived off government welfare.

“I couldn’t have written this book if I hadn’t had a few years where I’ d been really as poor as it’s possible to go in the UK without being homeless,” Rowing said in 2012. “We were on welfare, what we call welfare, I would call benefits, for a couple years.”

The experience helped define her political activism later in life. She frequently criticizes politicians who attempt to cut back on government welfare programs. She’s also talked about how the “single mother” label followed her throughout her career, and became the president of Gingerbread, a 100-year-old organization that supports single parents and their children.

“I was a Single Parent, and a ‘Single Parent On Benefits’ to boot. Patronage was almost as hard to bear as stigmatization.” she wrote in an essay. “I would say to any single parent currently feeling the weight of stereotype or stigmatization that I am prouder of my years as a single mother than of any other part of my life.”

She considered committing suicide.

It wasn’t an easy period for her. In a 2008 interview with the Sunday Times, Rowling said she was severely depressed and sought professional help.

“We’re talking suicidal thoughts here, we’re not talking ‘I’m a little bit miserable,'” Rowling said. “Mid-twenties life circumstances were poor and I really plummeted.”

Elsewhere, Rowling said that she used her experience of depression to describe the Dementors in her “Harry Potter” books.

“It was entirely conscious,” Rowling told The Times. “And entirely from my own experience. Depression is the most unpleasant thing I have ever experienced.”

Rowling has attended therapy sessions to treat her depression at other times in life as well, she told The Guardian, like during the period where she became very famous very quickly.

“For a few years I did feel I was on a psychic treadmill, trying to keep up with where I was,” she said. “I had to do it again when my life was changing so suddenly – and it really helped. I’m a big fan of it, it helped me a lot.”

In 1995, Rowling finished the first “Harry Potter” book and sent it to publishers — where it was roundly rejected.

Like many other authors, Rowling received a lot of rejection letters. Her book was accepted by Christopher Little, an “obscure London literary agent,” according to the New Yorker. Twelve publishers rejected it.

Rowling finally signed a deal with a small publisher that made her pick a pen name.

After a year, Little made a deal to print 500 copies of “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone” with Bloomsbury, a relatively young publishing company, and secured her a £2,500 advance.

The publisher anticipated that boys may not want to read books written by a woman, so it suggested she pick a pen name with two initials. The “J” stands for Joanne, her real name. She has no middle name, so she picked “K” for “Kathleen,” which was the name of her paternal grandmother.

“Philosopher’s Stone” appeared in print in 1997.

The book was a hit.

By March of 1999, 300,000 copies were sold in the UK. “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone” won numerous awards, including the Nestlé Smarties Book Prize, which is voted by both adults and children. In the United States, Rowling sold the book to Scholastic, which distributes it under the title “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone,” for more than $100,000, an unprecedented amount at the time. Then she bought her own apartment.

In 1998, Warner Bros. bought the film rights to the first two “Harry Potter” books.

“Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets,” the second book in the series, was sold in the UK in July of 1998, also to huge acclaim and sales. (It took another year for Scholastic to publish it in the United States.) In October, Rowling announced that she signed a seven-figure deal with Warner Bros. to adapt the books into movies.

By the time the movie series finished its run with “Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2” in 2011, it was the highest-grossing movie franchise of all time. But it was still a risk for the movie studio: No one knew when or how the series would end, and Rowling made significant demands over details like licensing toys with fast food companies.

The release of “Goblet of Fire” in 2000 represented a huge jump in popularity.

Rowling’s first three “Harry Potter” books – “Sorcerer’s Stone,” “Chamber of Secrets,” and “Prisoner of Azkaban” all made Rowling even more popular.

Writing her next book, “Goblet of Fire,” was an intense experience. At 636 pages, it was twice as long as “Azkaban” yet written in the same one-year timespan. Her publishers coordinated to release the book simultaneously around the world for the first time, putting pressure on her to finish it on deadline. During that period, Rowling was also involved in making the movie version of the first “Harry Potter” book.

After the book’s release, Rowling slowed down her writing pace. She told Bloomsbury she couldn’t write her next book in just one year.

“The pressure of it had become overwhelming,” she told the New Yorker. “I found it difficult to write, which had never happened to me before in my life. The intensity of the scrutiny was overwhelming. I had been utterly unprepared for that. And I needed to step back. Badly needed to step back.”

Rowling also later talked about how she hadn’t had time to process the level of her fame. She hadn’t (yet) purchased an expensive mansion or yacht; she’d been focusing on finishing her books and on her personal relationships. Taking some time to breathe was necessary for her mental health.

“I needed to stop and I needed to try to come to terms with what had happened to me,” Rowling told the Times of London in 2003. “I couldn’t grasp what had happened. And I don’t think many people could have done. The thing got so huge.”

After “Goblet of Fire,” Rowling kept writing, though. She published two short supplementary books in 2001 – “Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them” and “Quidditch Through the Ages” – the profits of which went to charity. “Harry Potter and Order of the Phoenix,” her longest book, was released in 2003.

The first “Harry Potter” movie made nearly $1 billion.

The 2001 movie adaptation of “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone” (or “Philosopher’s,” depending on where you lived) was a box office juggernaut. Starring Daniel Radcliffe as Harry Potter, Emma Watson as Hermione Granger, Rupert Grint as Ron Weasley, and a stable of classically-trained British actors rounding out the cast, it was an enormous undertaking. The Christopher Columbus-directed movie grossed $974.8 million at the box office and paved the way for what would become the most successful movie franchise in history.

A month after the movie’s release, she got remarried.

In a private ceremony, Rowling married Neil Murray, a Scottish doctor. (They had a son, David Gordon Rowling Murray, in 2003.)

She was so famous that she wore a disguise when she bought her wedding dress.

“I just wanted to be able to get married to Neil without any rubbish happening,” she told The Guardian.

Rowling makes sure she isn’t a billionaire.

In 2004, Forbes reported that Rowling was the first person to become a billionaire (in US dollars) by writing books. Later, she dropped off the list because she gave so much money to charity.

In addition to her creative work, she’s a major philanthropist.

Rowling has founded and supported dozens of charities with her fortune. In 2003, she said she sets aside one day a week to do “charity stuff.”

One of them is Comic Relief, an anti-poverty charity that gets the proceeds from sales of the “Quidditch Through the Ages” and “Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them” books. She is also the president of Gingerbread, which supports single parents, and she has donated millions to the study of multiple sclerosis, which her mother suffered from before her death.

Her biggest effort may be Lumos, named for the “Harry Potter” spell that conjures light. The organization seeks to end the institutionalization of children. All of the proceeds from sales of “Tales of Beedle the Bard” go to the charity.

Rowling also wrote and auctioned off a prequel short story from the “Harry Potter” universe, about James Potter and Sirius Black escaping a few muggle cops. The copy was later stolen.

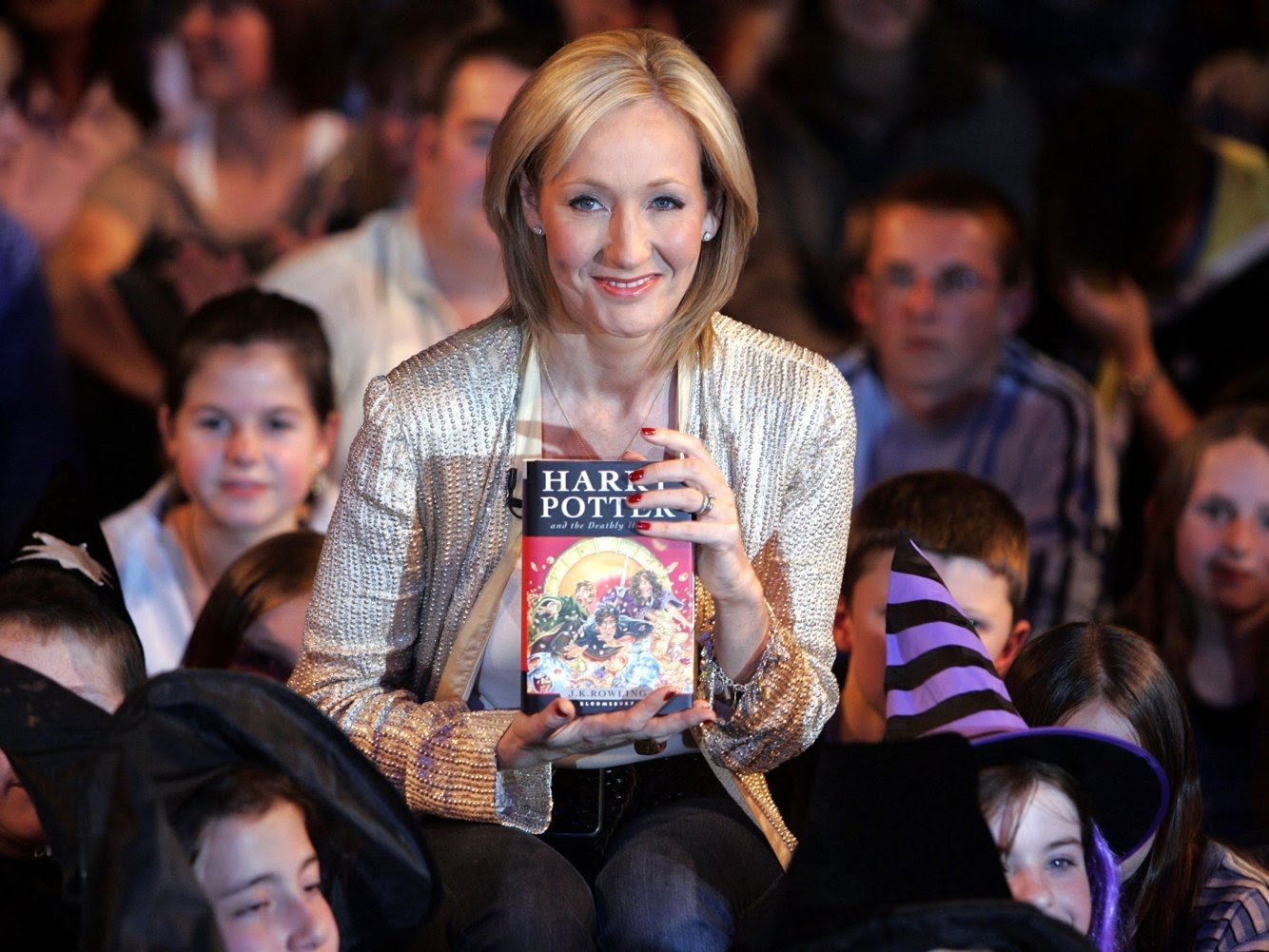

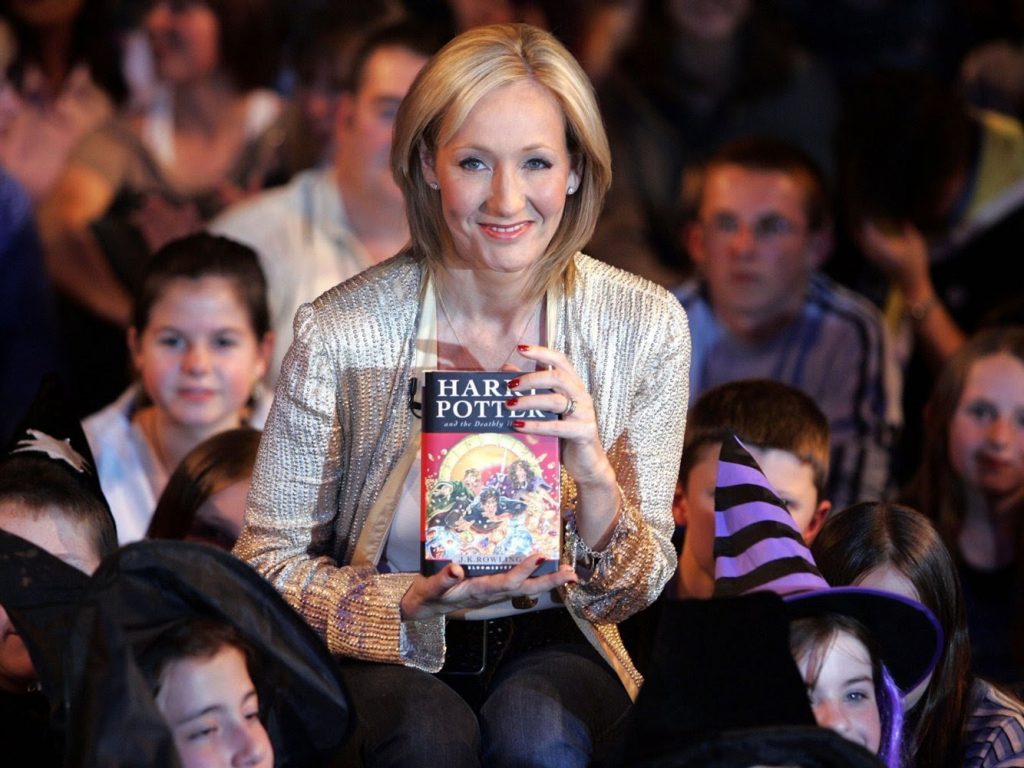

She finishes the book series in 2007.

In 2007, Rowling finishes the series with “Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows.” It is the fastest-selling book of all time. The seven books, in total, have sold more than 450 million copies and have been translated into 67 languages.

The year also sees the release of the “Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix” movie adaptation, and Rowling publishes “The Tales of Beedle the Bard,” a companion book to the series, in December.

Rowling was heavily involved with The Wizarding World of Harry Potter at Universal Studios, Orlando.

In 2010, Universal Studios opened The Wizarding World of Harry Potter, a theme park that recreated Hogsmeade, let attendants pick a magical wand, and ride a roller coaster through Hogwarts or on a Hippogriff. It’s so popular that attendance at Universal Studios increased by 66% at its first full year, and it’s now within striking distance of Disney, which ruled the theme park industry for decades.

Bloomberg reported that Rowling involved herself in every minutiae of the project, banning hamburgers, pizza, and Coca-Cola and instead ensuring that only British-style food would be served. Engineers proclaimed Rowling’s sketches for Hogsmeade’s wonky, surrealistic buildings as architecturally impossible, but eventually they figured it out anyway.

2011 is another major year for her: The last “Harry Potter” movie is released.

The eighth and last “Harry Potter” movie, “Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2,” (the final book was split into two movies) is released and breaks the record for the biggest opening weekend of all time. Radcliffe, Watson, and Grint say goodbye to the roles that will define their careers for the rest of their lives. It’s the end of a major chapter for “Harry Potter” and for millions of fans.

Then she released a treasure trove of trivia.

Rowling had long promised an encyclopedia that would index every factoid from her wide-ranging magical universe. In late 2011, it came in a different form than expected: as a website. Pottermore launched as a sort of hybrid game and “Harry Potter” Wikipedia, where users could sign up, get sorted into a Hogwarts house, and win points while also reading bits of information about different elements of the “Harry Potter” universe.

Some of the entries were illuminating, like the tragic backstory on Professor McGonagall. Others, like the ingredients that go into different potions, were more trivial. Still, it delighted hardcore fans. Since 2011, Pottermore has moved away from the game component and acted more as a depository for Rowling’s material. She’s expanded it, and added things like short stories about the founding of Ilvermorny, the American wizarding school, and a family history for Harry Potter.

The next year, Rowling released her first non-“Harry Potter” novel.

The release of “A Casual Vacancy” was anticipated with some uncertainty and trepidation. It was said to be about local politics in a small British town, and be decidedly about adult life and sex and other stuff that never made it into the books she wrote about child wizards. When it was released in September 2012, the reactions were mixed but mostly positive. Some dismissed it as an example of the limits of Rowling’s imagination, others praised it for an incisive, if sprawling, look at social issues that effect people living in the U.K.

She secretly wrote a book under a male pseudonym.

Reports surfaced in 2012 that Rowling was working on a crime novel, but the author stayed silent about what she’d write next.

In April of 2013, Little Brown published “The Cuckoo’s Calling,” about the fictional detective Cormoran Strike and his ambitious assistant Robin Ellacott. It was purported to have been written by a guy named Robert Galbraith. Reviews were good and sales were unremarkable.

A family friend of one of Rowling’s lawyers let slip that Galbraith was, in fact, a pen name for J.K. Rowling. On Amazon, sales of “The Cuckoo’s Calling” rose by more than 150,000%. She’s since written two more “Cormoran Strike” novels, “The Silkworm” and “Career of Evil,” and said she plans to write more “Strike” novels than “Harry Potter.” The books are being adapted into a miniseries for the BBC.

Throughout her career, Rowling has been politically active.

Rowling is known for her leftist political views, generally supporting Britain’s Labour Party (though she is not supportive of Jeremy Corbyn, the party’s current leader). She donated £1 million to the party in 2008 and frequently cites her experience living off of government benefits while she was writing “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone” when politicians threaten to cut funding for similar programs.

In 2014, Rowling, a citizen of Scotland, vocally opposed Scotland leaving Great Britain in the Scottish referendum. She donated £1 million to the campaign to stay. And in 2016, she campaigned against Brexit.

In 2016, Rowling released a “Harry Potter” prequel play and sequel movie.

Last year was another landmark year for “Harry Potter.” The play “Harry Potter and the Cursed Child” premiered in London, with a book version released around the world in July. Finally, “Harry Potter” fans had another chance to go to a bookstore at midnight and buy a new entry in the series.

The play was written with John Tiffany and Jack Thorne. Its story begins 19 years after the events of “Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows,” and it concerns the next generation of wizards that followed in the wake of Harry, Ron, and Hermione.

“It was 17 years and just because I’ve stopped on the page doesn’t mean my imagination stopped,” Rowling told The Guardian. “It’s like running a very long race. You can’t just stop dead at the finishing line. I had some material and some ideas and themes, and we three made a story.”

Later that year, the first movie in a spinoff series, “Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them,” was released.

Instead of outsourcing screenplay duties to Steve Kloves, who wrote the “Harry Potter” movies, Rowling wrote the screenplay for “Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them” herself. (Kloves remains a producer for the new series.) It takes place 70 years earlier than “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone,” and concerns the adventures of Newt Scamander, a “magizoologist” whose magical animals escape his enchanted briefcase while he’s on a trip in New York.

Starring Eddie Redmayne as Scamander, the movie was a box office and critical success. In the movie, Rowling expanded her universe even further, introducing new magical concepts and characters.

She plans four more movies in the series, and signs indicate that the storyline will eventually end up with Albus Dumbledore (to be played by Jude Law) dueling Gellert Grindelwald (played by Johnny Depp), an important event that foreshadows the “Harry Potter” series. Her screenplay was also published as a book.

Up next: More “Fantastic Beasts” movies, “Cuckoo’s Calling” books, and a worldwide tour of “Cursed Child.”

The next Cormoran Strike book, “Lethal White,” will arrive on September 18, followed by “Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald”on November 16. The most successful author alive isn’t stopping anytime soon.