Scott Catt seemed like an ordinary dad—hardworking, responsible, devoted to his son and daughter—but he had a very strange secret. And so did his children.

Just after sunrise on the morning of August 9, 2012, in the Houston suburb of Katy, Scott Catt, a fifty-year-old structural engineer, was awakened by the buzzing of his alarm clock in the master bedroom of the apartment he shared with his twenty-year-old son, Hayden, and his eighteen-year-old daughter, Abby. The apartment was in Nottingham Place, a pleasant, family-oriented complex that featured a resort-size swimming pool and a large fitness center.

Scott took a shower, dried off, and ran a brush through his closely cropped, graying hair. He put on a T-shirt, a pair of blue jeans, and some work boots and walked into the living room, where Abby and Hayden were waiting for him on the couch. Hayden was also wearing a T-shirt and jeans, along with some slip-on tennis shoes. His short dark hair was brushed forward, splayed over his forehead. Abby, whose highlighted blond hair fell to her shoulders, was wearing a blouse, black yoga pants, and flip-flops.

“Okay, kids,” Scott said. “You ready?”

Hayden and Abby both nodded. The family headed out the back door and walked toward Abby’s 1999 green Volkswagen Jetta in the parking lot. Scott was a big guy, six-foot-four and 240 pounds, and he had to bend forward at the waist and duck his head to squeeze into the Jetta’s passenger seat. Hayden, who was six-two and 200 pounds, crammed himself into the backseat, pulling his knees up to his chest.

Abby started the car, pulled out of the complex, and made a couple of turns. In five minutes, she was driving into the parking lot of a strip center filled with small businesses—Fitness Unlimited, Shipley Do-Nuts, Weddings by Debbie, RadioShack, and Texas Mesquite Grill, among others. Abby parked the car about fifty yards from a Comerica Bank.

Scott grabbed a black garbage bag from the floorboard and took out two pairs of white painter’s coveralls, two white painter’s masks, two pairs of blue latex gloves, and two Airsoft pistols, which look like real guns but shoot only plastic pellets. In the tight confines of the Jetta, he and Hayden squirmed as they put on the disguises. Scott clipped a walkie-talkie to the lapel of his coveralls and handed another one to Abby.

It was nine-thirty. For the next thirty minutes or so, they sat in the Jetta, staring at the front door of the bank. Finally, Scott said it was time for them to make their move. Abby dropped her father and her brother off a few stores down from the bank and then drove around to an alley in the back. Just minutes later her dad’s voice crackled through her walkie-talkie.

“You there, Abby?” he said. “We’re going in.”

Robbing a bank is the most traditional of crimes. It’s a simple and direct act with an immediate payoff. All sorts of criminals have tried it—from professional stick-up men with long, violent pasts to drug addicts who just need money for a fix. Grandfathers have robbed banks, as have desperate housewives. “If you’re in law enforcement long enough, you’ll eventually come across bank robbers of every shape and size,” said Troy Nehls, the sheriff of Fort Bend County, which includes part of the Katy area. “But I’m not sure there has ever been a bank-robbing family. And then along comes Scott, Hayden, and Abby.”

By law enforcement standards, the Catts were as unlikely a set of bank robbers as one could imagine. They had no pressing financial issues and no obvious personal problems. Scott worked for a Houston energy company, helping to design conveyor belts that transport petroleum coke. Abby was a salesclerk at the Victoria’s Secret at the nearby Katy Mills Mall, and Hayden was hoping to start a career as a hotel concierge. (Beth Catt, Scott’s wife and the mother of Abby and Hayden, had died of breast cancer many years earlier.)

Around the Nottingham Place apartment complex, the Catts were regarded as friendly and harmless—“just like regular, everyday people,” one neighbor said. In the evening, the three of them could be seen sitting on their small patio, talking quietly among themselves. Before night fell, Scott often took their dog, a yellow Lab named Bella, on walks around the complex, circling the various apartment buildings.

Yet when it came to robbing banks, said Nehls, “they were very bold, very daring, and very risky. They’re lucky they didn’t get caught up in a shoot-out.”

The Catts pulled off only two robberies: the first being the Comerica heist, which netted them close to $70,000, and the second one coming two months later at First Community Credit Union, on Katy’s Cinco Ranch Boulevard, where they got away with $30,000. On the morning of November 9, five weeks after the second robbery, they were getting ready to rob a third Katy bank when Nehls’s detectives, who had conducted some nifty investigative work, arrived at Nottingham Place and arrested them

Usually such a brief crime spree would merit little attention, but news of the Catts’ arrests instantly went viral, with their mug shots showing up in publications and on websites around the world under headlines like “All in the Family” and “A Family Affair.” Stories circulated that the elder Catt had started robbing banks a decade earlier in Oregon, where the family had previously lived, and that after he had moved to Texas he’d started using his son and daughter as his accomplices. Reporters did their best to find out why a father and his two children would turn to bank robbery, but the Catts weren’t talking. Then, in late 2013, after months of negotiations, the three of them agreed to plea deals, and they consented to let me interview them.

I was allowed to speak to only one Catt at a time. Abby was the first one escorted to the visiting room. Wearing a uniform with horizontal black-and-white stripes, she sat on a plastic chair, gave me a soft look, ducked her head, and finally said after a silence, “Sometimes I feel so embarrassed about what’s happened that I just want to disappear.” Hayden came in next, taking a seat in the plastic chair and gently crossing his right leg over his left at the knee. “Every night I stare at the ceiling and I ask myself, ‘What were we thinking?’ ” he said.

Then I got the chance to talk to Scott. He gave me a firm handshake, sat down, and began pushing his fingertips together. “All I can tell you is that I thought it would help us as a family,” he said.

“Robbing banks would help you as a family?” I asked.

Scott took a breath and slowly blew it out. “I did it for the family,” he said. “I swear to you, I would only rob banks for my family.”

The story begins in the small town of McMinn-ville, Oregon, forty miles southwest of Portland, where Scott was born and raised. His father was a loan officer at First Federal Savings and Loan. At McMinnville High School, Scott played on the football team. He fell in love with Beth Worral, the star of the school’s swim team, and they married after graduation. In college, Beth studied marketing and Scott studied drafting and engineering. After Beth gave birth to Hayden and Abby, they built a four-bedroom house in the town of Dundee, in the heart of Oregon’s wine country—“our dream house,” Scott told me. But in 1995 Beth was diagnosed with breast cancer. When she died, in February 1997, Hayden was five and Abby was two.

At that point, Scott told me, “life sort of came to a halt.” Unable to cope with his grief, he began drinking heavily. He married again in 1998, but it was over within fourteen months. He got a couple of DUIs and checked himself into rehab. He fell behind on his house payments, and eventually he and his children moved in with his mother. (His father, by then, was deceased.) He went through a couple of jobs. His car was repossessed.

Sometime between 2000 and 2002, he began thinking about moonlighting to make some extra money. He remembered a long-ago day when his father had come home and said that First Federal had been robbed by a man in a mask. When Scott asked why no one had tried to stop the robber, his father replied that the tellers had been trained to comply whenever a robbery took place, because the money was insured. The bank would get it back.

One morning, after dropping off the kids at school, Scott drove his pickup truck to a branch of his dad’s old bank that was just a couple of blocks from where they lived. He strode into the lobby wearing a ball cap, black sweats, a white painter’s mask, and sunglasses. He was carrying a trash bag and an antique pistol—unloaded, he told me. He went straight up to a female teller’s window, demanded all her money, and ordered her not to add any bait bills or dye packs. The teller dumped around $2,500 into his bag. Scott walked briskly back to his truck, drove around for a while to see if he was being followed, and headed home.

A couple of days later, the McMinnville newspaper published a grainy black and white frame from the bank’s surveillance video showing the robber. “My mother said the man in the photo looked a little like me, and I just laughed,” Scott said. “And that was it. We all went out for dinner that night. The police never came to knock on my door.”

Scott did his next job a year later, after falling behind on some bills. Wearing a similar disguise, he burst into another small branch bank in McMinnville, waved his pistol at a teller, got $1,500 from her drawer, and slipped away as quickly as he’d come in.

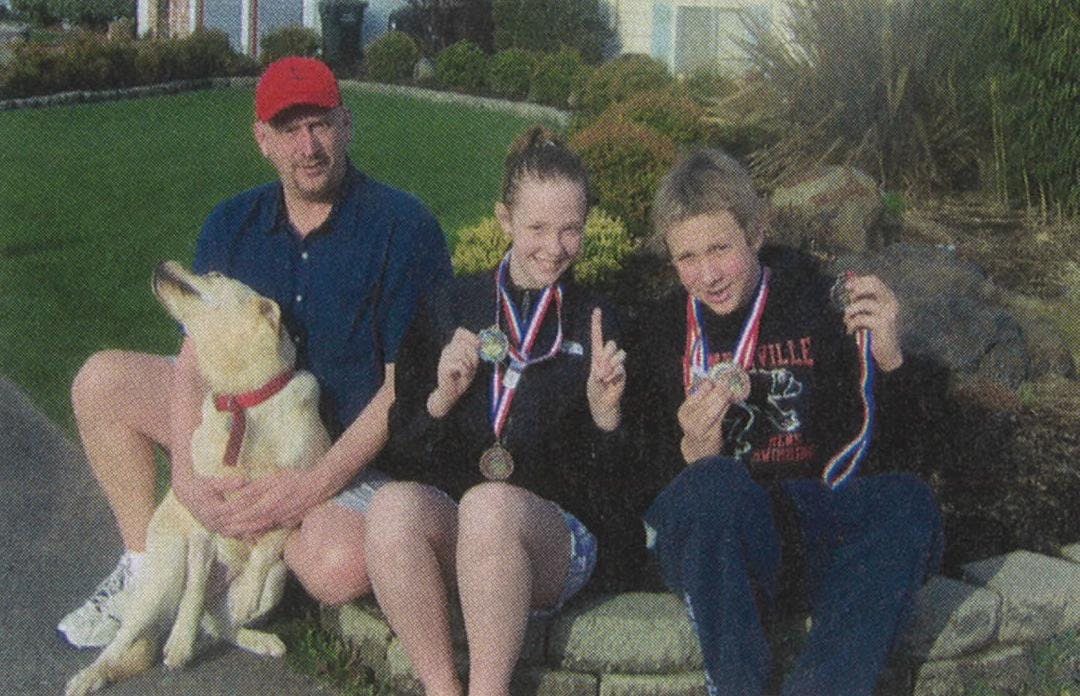

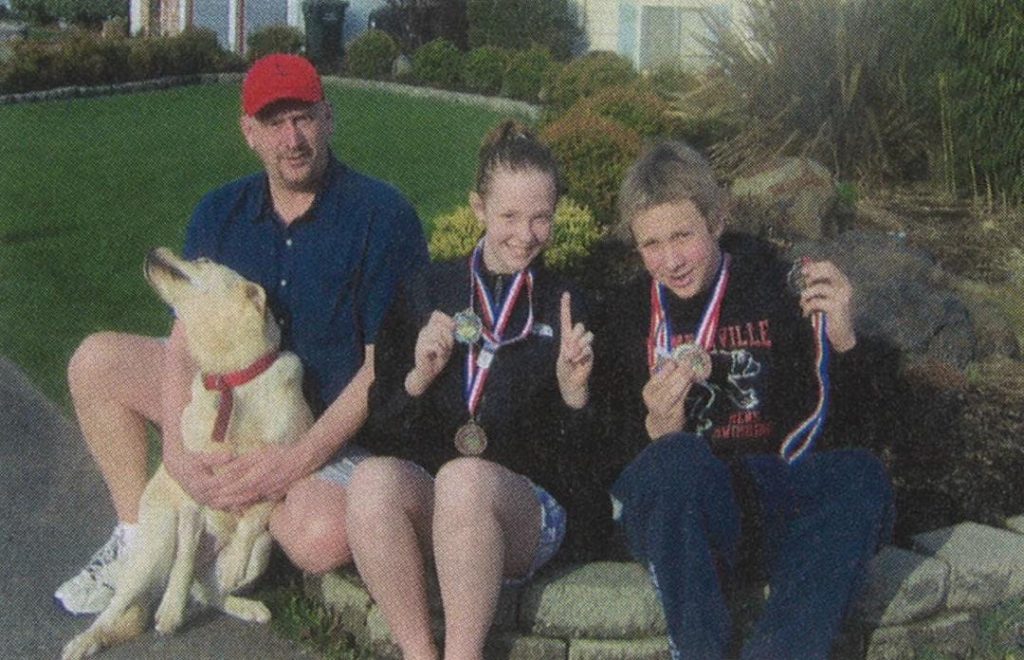

Eventually, Scott landed a job with an engineering company located just outside Portland, earning $25 an hour. But once a year or so he would hit a bank, hauling in between $5,000 and $10,000. (Law enforcement authorities now believe he robbed at least five banks in Oregon.) It had become part of his life. “I didn’t feel like a criminal,” he told me. “I didn’t load my pistol. I knew I wasn’t going to shoot anybody. And I kept telling myself that whatever money I got was insured, so who was really being hurt?” Meanwhile, around McMinnville, Scott maintained a reputation as a devoted single father who always put his motherless children first. He cooked them dinner almost every night and took them on summer vacations (they loved going to amusement parks throughout the country to ride roller coasters). When the kids got interested in competitive swimming—they focused on the backstroke, which had been their mother’s favorite event—Scott signed them up at the McMinnville Swim Club and drove them to practice every day, eventually becoming the club’s president. Kathryn Lundeen, who served on the club’s board, would later tell a Portland newspaper that Scott “showed a lot of leadership. . . . I liked the guy. He never struck me as being a person who had poor judgment.”

***

Abby and Hayden both told me that during this period, they never once suspected that their father had any sort of secret life. They never questioned the fact that he sometimes had a thick wad of $100 bills in an envelope in the dresser drawer of his bedroom. “Even if he was robbing banks, which we didn’t know about yet, Dad still worked really hard at his engineering job,” said Hayden. “He’d be up and gone to work by four-thirty or five in the morning. He didn’t make great money, but we always appreciated how hard he worked to keep us afloat. And we appreciated how he was home on time every day to take us to swim practice. He didn’t stop at a bar and drink.”

“Dad was a great motivator,” Abby told me. “At the beginning of each season, he pushed me to work hard and set goals. He told me I could be somebody. The night before every swim meet, he would cook us pork chops, noodles, applesauce, and a protein shake. I loved it. I thought our lives were good.”

One year, Hayden qualified for the high school state swim meet. There was even talk that he could get a college scholarship in the sport. But by the age of seventeen, he told me, he was drinking too much—sometimes blacking out five nights a week—and he quit swimming altogether. He had started to come to terms with the fact that he was gay, and he didn’t know how to tell his friends and family. “Alcohol was the way I dealt with that,” he told me. “Honestly, for a while, I hoped I would pass out and not wake up. I was scared of a lot of things.” The following year, he did come out to his dad and sister, who were both accepting.

As for Abby, she lost interest in swimming when she turned fifteen. She started running with what she called “the drinking, partying crowd.” Scott sat her down and told her that she needed to pull it together, but, according to Abby, she wasn’t ready to listen to him. Before long, she ended up in an alternative school, taking online classes. After graduation, Hayden found work as a hotel bellman and a weekend tour guide, driving people around to see the local wineries, but he was still drinking too much. And Scott was again falling behind financially, living paycheck to paycheck. By 2010, it was time to do another bank robbery.

Scott knew that if he had a bigger operation—“a team of accomplices” was the way he put it to me—he could get cash from several tellers’ drawers and perhaps even get to the bank’s vault. The problem was that he had no criminal friends to turn to. There was no one he could trust to stay quiet about what he was doing—except for his own children. Maybe, he began to think, he should talk to Hayden and Abby about joining him.

He quickly rationalized the idea to himself. For one thing, he knew that as long as they did what he told them, they wouldn’t get caught. And he would use the money from the robbery to start a small business—maybe a coffee shop—that he’d let the kids run. “They were floundering,” he told me. “I could see the despair in Hayden, and I thought he could use—I don’t know—some inspiration, some excitement. Same with Abby. She had lost her self-esteem, not graduating from high school. All I can tell you is that I thought doing it would give us all a little boost in our lives—that it would help us as a family.”

He first approached his son. “We were sitting at the kitchen table,” Hayden recalled. “I was having some coffee, and he said he had something important to tell me. He said he had a second job as a part-time bank robber. The way he looked at me, I knew he wasn’t kidding.”

Scott told him he had never come close to getting caught. He mentioned that he had even robbed a bank across the street from a natatorium where Hayden and Abby had been swimming in a meet. “He said he popped over to the bank, robbed it, ran back across the street, and put the money in a duffel bag of mine in the locker room,” Hayden said.

Scott asked Hayden to join him. He said he would be the “muscle,” leading the way in, scaring and subduing the employees and customers, and Hayden would be the “bag man,” heading for the tellers’ counter and ordering them to put all their money into his black garbage bag.

Hayden was aghast. “But Dad,” he said, “I’m gay!”

“Yeah, but if you cover up your baby face, you can be intimidating,” Scott assured him.

Hayden asked his father why he didn’t recruit one of his friends to be his bag man.

“Who else can you trust except family?” Scott said.

Scott drove Hayden to a bank in a Portland suburb. He had him walk inside so he could see for himself that there were no armed guards. He told him they would dress in coveralls and painter’s masks, barge into the bank early in the morning before there were too many customers, grab what money they could, and be out within three minutes. They would then jump into Scott’s truck (with stolen license plates taped over his real license plates) and disappear into a nearby neighborhood, where they would take off their disguises and throw them in a dumpster. Scott promised Hayden they could easily get away with $40,000, probably more.

But on the morning they planned to do the robbery, Hayden was too scared to leave the house. Disappointed, Scott simply did the robbery himself, getting a few thousand dollars out of one teller’s drawer. He was home before lunch. “He did it so quickly and so easily that it planted a seed,” Hayden told me. “I thought, ‘My dad really does know what he’s doing.’ ”

Before they could plan another heist, however, Scott got laid off from his job and decided it was time to try his luck elsewhere. He connected with a Texas recruiter who specialized in engineering, and in January 2012 he moved to Houston to work for a division of Kinder Morgan. The kids stayed behind. Abby moved in with her grandmother, and Hayden eventually relocated to Hawaii, where he got a job at a resort hotel. It seemed like the beginning of a new era for the family. Scott’s job in Houston paid $40 an hour—a huge leap from his Oregon salary—and he hoped he would finally be able to quit thinking about banks. He wasn’t. There were just so many in Texas. They seemed to be on every other street corner, beckoning to him. He found himself slowly driving by the banks, the old itch returning.

He called Hayden and said, “You wouldn’t believe it out here. There are banks everywhere. Beautiful banks.”

“I said, ‘You’re not thinking about it, Dad, are you?’ ” recalled Hayden. “He said, ‘Once, maybe twice, just to get us ahead.’ ”

By March, Scott had persuaded Abby to join him in Texas. Hoping to get a fresh start, Abby arrived in Katy and landed a job at Victoria’s Secret. (She proudly announced on her Facebook page that she was a Victoria’s Secret “Pink Girl.”) A few months later, Hayden decided to join them. He wasn’t sure he was going to like Texas at first, but then he attended the annual gay pride parade in Houston’s Montrose neighborhood. “I thought, ‘Texas really is the promised land,’ ” he told me. He applied for jobs as a hotel concierge. But it wasn’t long before he began talking to his father about doing a bank robbery. He said he wanted to get some money together to go to college.

Scott already had a bank picked out: a Comerica in a nearby strip center. He began walking past it in the mornings with Bella, to see when the bank got busy, and he had Hayden go into the bank and fill out forms for a checking account, all the while looking around so he could get a layout of the lobby.

The more they studied the bank, though, the more they realized they needed a getaway driver. And there was only one person who came to mind.

One evening, Hayden went into Abby’s bedroom. She was sitting on her bed listening to Snoop Dogg. “I need to tell you something,” said Hayden. “Dad’s a bank robber, I’m going to become one too, and we want you to join us.” Showing off a term he had picked up from the Internet, Hayden said, “We want you to be our wheel man.”

“You want me to be a what?” asked Abby.

The next day, Scott had his own talk with Abby, promising her that all she’d have to do was drop them off in the parking lot, wait patiently for them to return, and drive at a normal speed back to the apartment. If there were cops driving by, he said, they would ignore her.

Abby felt she had no choice but to participate. Her father and brother had been all she’d had since she was two years old. “This was something I felt like I had to do, to protect them, to make sure they got out of the bank and didn’t get shot or something,” she told me. “I didn’t want to let Dad down.”

In the apartment, while Abby sat on the couch eating potato chips, Hayden and Scott practiced their bank-robbing routine, pretending to burst into a bank and yell at everyone to get their hands up. Hayden, who had never in his life held a gun, pointed his Airsoft pistol at an imaginary teller as he cried, “We just want the money! Everyone act cool! No dye packs and no GPS devices!”

They scheduled the robbery for August 9, because that was Abby’s day off from Victoria’s Secret. The night before the robbery, Scott had Abby and Hayden go to another apartment complex, steal the license plates off a car, and put them over the Jetta’s plates. The next morning, as they headed out the door, he told his children that everything was proceeding perfectly.

Abby, however, was terrified. “I said, ‘Dad, I’m totally freaking out,’ ” she told me. “I knew my life was about to change forever.” Hayden was so anxious that he downed an airplane-size bottle of Jack Daniel’s whiskey to calm his nerves. It didn’t help. When he followed his dad into the bank, his hands were shaking so much that one teller had to help him open his garbage bag so she could give him the money from her drawer.

Nevertheless, the robbery went off exactly as planned. After emptying the tellers’ drawers, Scott and Hayden got to the vault and grabbed stacks of money off the shelves. Outside, Abby was giving them time updates over the walkie-talkie:

“Thirty seconds . . . one minute . . . one minute thirty.” At the three-minute mark, Scott and Hayden ordered the bank manager to unlock the back door and out they went, jumping into the Jetta. Abby was dying to hit the accelerator, but she followed her dad’s instructions, driving slowly, obeying all traffic signs. She stopped at a dumpster behind a restaurant, where Hayden and Scott threw away their disguises, pistols, stolen license plates, and gloves. They got back to the apartment, emptied the garbage bag, and stared wide-eyed as the money fell to the floor. They had hit the jackpot, close to $70,000—a stunning haul coming from a little branch bank.

They heard sirens and decided to get out of their apartment. Scott took a ride on his motorcycle, Hayden went shopping for clothes, and Abby went to the VIP Nails Salon for a manicure—“to get my mind right and relax,” she told me. That night they had a celebratory dinner at Chuy’s. Abby was still too nervous to eat—“I kept looking at the door, waiting for the police to walk in,” she said—but Hayden was overjoyed. “I felt exhilaration, the most intense high I’ve ever experienced,” Hayden said. “It changed my life. I’ll be truthful about that.”

Scott paid off several overdue bills. He bought himself a second motorcycle for about $10,000, and he bought Hayden a $17,000 Tahoe and Abby a $12,600 Ford Focus (the Jetta had been having engine trouble). He and the kids then split up what was left. By late September, all the money had been spent on groceries, restaurants, clothes, furniture, and, as Scott said, “some partying.” They had not socked any money away to open that coffee shop.

He and Hayden began driving around, looking at more Katy-area banks. They finally settled on First Community Credit Union, which was close to a country club, and they told Abby they needed her to be the wheel man one more time. “I remember Abby looking at us and saying that we could be the family in Breaking Bad,” said Hayden. “Except no drugs and no one got killed.”

Because there was a construction crew working on a road near the bank, Scott sent Hayden and Abby to the Home Depot to buy two orange safety vests for disguises. (Hayden also went to a costume shop to buy a fake black mustache because he didn’t like wearing a painter’s mask.) On October 1, Abby took a day off from Victoria’s Secret and drove her brother and father to the credit union. Scott and Hayden entered the bank at about 1:50 in the afternoon and put on another flawless performance. Their size and the guns terrified everyone. This time, Hayden’s hands weren’t shaking. According to an employee, he yelled at a teller, “Is this all you got? I’ve got bills to pay!”

They were in and out of the bank so fast that no one was able to get a good look at the car. As Abby drove down Cinco Ranch Boulevard, back to the apartment, Scott and Hayden ducked their heads as several police cars came screaming from the opposite direction. Not one officer gave Abby a second look. All they had heard over the radio was that two tall men had committed a robbery. As Scott had predicted, the last person the cops were looking for was a teenage girl.

The Catts got $29,953 out of that robbery—a decent sum. Afterward, Hayden went straight to an urgent care clinic (it turned out he was coming down with mono); Abby went to her nail salon, but she couldn’t relax. A few days later she told her father that she couldn’t deal with the stress of being a bank robber. She said she wanted to take her cut of the money and move into her own place. Scott promised to get her an apartment but begged her to remain their wheel man. He told her he needed her more than ever. After the first robbery, he had decided to quit his engineering job and make a living as a full-time bank robber, and Hayden had decided to join him.

“The greed had snowballed,” recalled Hayden. “I had become consumed with money: spending it, getting more. I wanted to rob enough banks until I could afford to go back to Hawaii and live out the rest of my life in a grass shack. It was all I thought about, like an addiction.” In early November, Hayden and Scott told Abby that they had found their third bank to rob. They planned to wear suits, to blend in with the businessmen who worked in the surrounding offices. On November 8, Abby drove them to the bank, but there was too much foot traffic, so they decided to call it off. The next morning, Scott and Hayden were preparing to try again when officers from the Fort Bend County Sheriff’s Office came knocking.

While studying the video of the First Community Credit Union robbery, Jeff Martin, a thick-set veteran detective with the sheriff’s office, had noticed that the safety vests worn by the two robbers weren’t in any way tattered or dirty. In fact, he was certain he could see creases in the vests from where they had been folded in their original packaging. He did some online searches, looking for stores that sold that particular style of vest, and he came across one on the Home Depot website. Martin went to a judge, got a subpoena to review purchases at several area Home Depots, and learned that just before the credit union robbery, two such vests had been purchased at a Home Depot in Katy with a debit card belonging to one Scott Catt. A search through security footage from the store turned up images of a young man and a blond teenage girl buying the vests. After doing a background check on Scott, Martin learned that he had two children named Hayden and Abby, whose photos matched the two people buying the vests.

Martin quickly figured out that Scott and Hayden were the robbers in the video and that Abby was the one whom tellers heard counting out time intervals over a walkie-talkie during the robbery. His case was bolstered when he found video of Abby applying for an account at the credit union a few days before the robbery. (Scott had sent her in there to scope the layout.) He had the Catts arrested and placed in separate interrogation rooms at the sheriff’s office.

Martin decided to first talk to Scott. He assumed that like almost all criminals he had dealt with, the elder Catt would vehemently declare his innocence, claiming a case of mistaken identity. But before Martin even got the chance to lay out the evidence he had against him, Scott quickly confessed all, going so far as to talk about his Oregon robberies, which Martin knew nothing about. He tried to explain to Martin in psychological terms why he started robbing banks. “You can go back to when my wife passed away,” said Scott, as somber as an owl. “You really can—when my life spiraled down to DWIs and self-loathing.” Martin just stared at him, dumbfounded.

Martin seemed equally dumbfounded as Hayden and Abby gave their own confessions. Wearing a gray hooded sweatshirt, black yoga pants, fuzzy black-and-white slippers, and black sunglasses propped on her head, Abby broke into tears trying to explain her loyalty to her father. (“He’s always done the best for me, and he’s always been there for me,” she said.) When Hayden was asked if his father had ever discussed with him and his sister what would happen to them if they were caught, he stared at the detective, his face bewildered. “No,” he finally said in a strained voice.

Although the getaway driver in a bank robbery is liable under Texas law for the same punishment as the bank robbers themselves, the police and prosecutors felt some sympathy for Abby, and they agreed to her attorney David Ryan’s request for a very mild, 5-year sentence. (Eligible for parole in eighteen months.) They also agreed to give Hayden a 10-year sentence. (His parole would come up in just under 4 years.) But they lowered the boom on Scott, hitting him with a 24-year sentence, which he finally agreed to take to avoid a potentially harsher sentence at a jury trial.

When I talked to Scott, he was seventy pounds lighter than he’d been on the day of his arrest, which he mostly attributed to “a lot of remorse” for what he had done to his children. He added, “When I look back on what I did, what led to this place, I would have been better off—we all would have been better off—if I had gone on welfare and been a stay-at-home dad.”

As for Abby and Hayden, they didn’t seem to know what to think of their father. “He should have been protecting me, instead of the other way around, having me protect him,” Abby said, a forlorn look on her face. But a few minutes later, she mentioned that she had accidentally run into her father just a day or so earlier in the county jail’s infirmary. “He told me he loved me, to be strong, and to be patient. And then he said he was so sorry. I broke down and started crying. I mean, like I’ve said, he is my dad.”

Abby plans on becoming a nurse, her lifelong dream, when she is released. After he serves his sentence, Hayden wants to go to college and get a degree in advertising, architecture, or engineering—“that’s right, engineering, like my dad,” he said with a smile.

Scott told me that his one hope for the future is that his children will come visit him when they are free. “I heard that maybe the state prison will let me do a hardship thing, spend a weekend with Abby and Hayden.” When I told him that I did not believe the Texas Department of Criminal Justice had such a program, he sighed and told me he’ll be 62 years old when he’s first eligible for parole.

“If I get out, I want to have a homecoming dinner that night, me and the kids,” he said. “We’ll go to a good restaurant, tell stories about the old days.” He paused.

“About the days when we were a family.”